Ultrasonic Flow Measurement System Improves Control at Reading WWTP

By John Gerberich and Alan Vance

The wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) in the city of Reading, Pa. (see Fig.1), receives wastewater from the city and its 11 surrounding communities. Four remote pumping stations pump wastewater to the plant, which processes 28.5 million gallons per day.

If Reading's WWTP has a mission statement for its day-to-day operations, it couldn't be simpler or more critical: 95°F. That's the optimal temperature at which the anaerobic bacteria in the facility's three 800,000-gallon digesters most efficiently process the waste stream. The problem, however, was that the parameters needed to control the system accurately couldn't be measured, and it was costing a great deal of money.

Manual Measurements Didn't Work

At 95°F, the digesters generate a wet biogas flow that averages 3,500 standard cubic feet per hour, with a methane fraction of 65 to 70 percent (the methane is used as fuel for three boilers). Each boiler is paired with a digester, providing the heat needed to keep the temperature constant, even in subzero winter weather.

A steady flow of wastewater sludge is fed to the digester, where it is consumed by bacteria that thrive in an oxygen-free environment. The bacteria generate biogas, which mainly consists of methane and carbon dioxide, along with a very small fraction of other gases. The methane then fuels the digester's boiler, which heats the digester, keeping the bacteria productive.

Previously, Reading's WWTP was using an outdated pressure transducer to monitor biogas flow, and its poor accuracy often caused false readings. Temperature was monitored manually, while the facility's lab analyzed gas samples to determine the methane fraction. Based on this data, operators would feed sludge to the digesters.

The daily analysis took up to four hours per day in technicians' time and caused large latencies in adjusting the sludge flows into the digesters. Sometimes the methane fraction would drop below 20 percent, and the temperature would fall to 80°F. This would not only slow the plant's throughput but also increase costs.

When these conditions occur, a digester can sour, causing the bacteria to produce higher levels of other gases that can accelerate the corrosion of metal parts in a plant's plumbing -- the piping, regulators, etc. What's more, if the methane fraction falls too much, staff must tap external sources of natural gas to fuel the boilers, which can cost up to $16,000 per month.

Reading staff needed to optimize the digester cycle through constant monitoring of the gas flow, temperature and methane fraction to keep all three parameters within the plant's preset operating limits.

Ultrasonic to the Rescue

A thermal mass flowmeter, also known as a thermal dispersion flowmeter, would be an improvement over the plant's pressure transducer, but it would not be ideal. Thermal mass flowmeters are well suited for measuring dry gas flows but not the kind of wet, dirty biogas generated by the anaerobic digesters.

A thermal mass flowmeter measures the flow rate by monitoring the cooling differential between the heated sensor and the measurement sensor. The plant's biogas could cause condensation on the two sensors, which would result in inaccurate readings. Further, the condensation coupled with trace acid vapor and particulate matter could foul and corrode the sensors, requiring periodic maintenance and eventually replacement of the sensors.

Reading staff sought a way to measure temperature and methane fraction in real time, which would enable them to dispense with time-consuming lab testing. They installed an Endress+Hauser Proline Prosonic Flow B 200 instrument (see Fig. 2) to measure both parameters, display them (and other parameters) locally, and transmit this measured data back to the control system via a 4-20 mA connection. B 200 is an ultrasonic flow measuring system specifically designed for real-time monitoring of wet, dirty biogas with variable composition at low flow and pressure.

The B 200 has an accuracy of ±1.5 percent of flow, independent of gas composition, and it continuously calculates methane fraction, calorific value and energy flow. Because it has no moving parts, the flowmeter is maintenance-free and self-cleaning.

How It Works

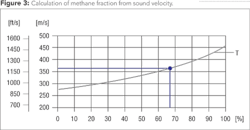

The sound velocity, temperature and chemical composition of a gas are directly related to one another. If two of these characteristic quantities are known, the third can be calculated. The higher the gas temperature or the methane fraction, the higher the sound velocity is in biogas (see Fig. 3).

Since the instrument accurately measures both the sound velocity and the current gas temperature, the methane fraction is calculated directly and displayed onsite (see Fig. 4) without the need for an additional measuring instrument.

The relative humidity of biogas is usually 100 percent. Thus, the water content can be determined by the temperature measurement and can be compensated for in the measurement. The B 200 (see Fig. 5) is unique in its ability to measure the methane fraction directly, making it possible to monitor the gas flow and gas quality 24/7.

With the new ultrasonic meter, Reading's WWTP operators now receive real-time measurement of the digesters' biogas flow, temperature and, most importantly, methane fraction. By monitoring the set points of this data in real time, technicians can adjust the sludge fed to the digesters much more precisely without waiting hours for the lab's test results.

Due to fewer required man-hours for sampling and lab testing, the plant's labor savings are approximately $20,000 per year -- time technicians can devote to other tasks. In addition, because the B 200 helps them better gauge and control the methane fraction, corrosion and wear and tear on the boilers is reduced.

The plant has also been able to cut teardown maintenance in half, saving another $15,000 per year. The biggest savings, however, come from minimizing -- if not eliminating -- the need for external natural gas to fuel the boilers. Before, the plant would have to supplement its methane fuel in cold winter months at a cost averaging $37,500 per year, which has been greatly reduced.

Better measurement of critical operating parameters at Reading's WWTP has cut fuel costs, reduced required maintenance and increased overall operating efficiency. Keeping costs down has also allowed staff to keep rates reasonable for customers, and the reduction in maintenance has allowed the utility to redeploy valuable internal personnel to other tasks, which will further improve operations.

About the Authors: John Gerberich has been the chief electrical engineer for Reading's WWTP for 25 years. His primary responsibility is to keep the plant in compliance through the use of state-of-the-art instrumentation to control critical processes, which are monitored by a SCADA system that automatically adjusts equipment. Other duties include emergency generation, high/low voltage distribution, PLCs, communications, and backup systems for critical areas.

Alan Vance is the industry manager for wastewater at Endress+Hauser and has 25+ years of experience in process control instrumentation.

More WaterWorld Current Issue Articles

More WaterWorld Archives Issue Articles