Water Resilience in a Changing Climate

By Randi Minetor

In October 2012, a massive storm surge demonstrated its potential for destruction in a major metropolitan area when Hurricane Sandy tore through New York City. The storm’s force destroyed neighborhoods and businesses, shut down global commerce on the New York Stock Exchange, and brought the city’s public transportation system to a grinding halt. In the space of a few days, New York City officials and residents understood their vulnerability better than ever before. If the city did not take action to protect its people and infrastructure in the very near future, damages could continue to mount as climate change sends more major storms up the east coast.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) responded quickly after the initial crisis had passed, launching a competition to find the best ways to protect the northeast coast from the storms that were certain to follow. The competition, dubbed Rebuild By Design, produced six winning proposals for the protection of coastline throughout the New York metro area. Already the projects have received $176 million in funding from HUD’s National Disaster Resilience Competition, and another $100 million from the City of New York.

One project in particular will protect Lower Manhattan, following the island’s perimeter in a “Big U” from West 57th Street south to the Battery and up the east side of the island to East 42nd Street. During the planning process, project leaders Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) reached out to stakeholders throughout the area, holding workshops that engaged the community and encouraged debate as participants examined a wide range of approaches. BIG extended its inquiry to city, state and federal agencies, elected officials, and planning boards, bringing as many people to the table as it could to fully grasp what the community felt was important to the project. The result of this effort is full engagement by stakeholders - not only in a competition-winning proposal but in the energy and commitment it will take to make the Big U a reality for this globally important section of Manhattan.

This kind of collaborative effort is exactly what a new report by Arcadis calls for as a central component to any city’s strategy for resilience. The 2016 Sustainable Cities Water Index, released in April, examines 50 cities around the world, selected for their “distinctive water relationships that helped shape their urban character and define their commercial identity.”

More Work to Do

The report reveals that most cities need to improve their resilience in the face of extreme weather events and climate change - including the nine American cities examined in the index: Washington, D.C., New York, Houston, Boston, Philadelphia, Dallas, Chicago, San Francisco and Los Angeles. All have work to do to ensure that the water supply and treatment facilities remain stable in any situation, and that the cities are well protected from the impact of storm surges, heavy rains, and drought.

In these cities, Arcadis found issues that can affect the water supply over the long term: system leakage and accountability for water usage. “There is a very mixed picture when it comes to this with many developed economy locations’ aging infrastructure seeing the effectiveness of their systems suffer,” the study noted. “Being developed in other ways doesn’t necessarily translate to a sustainable use of resources … To achieve long-term viability, city leaders need to pay close attention to each area of water sustainability.”

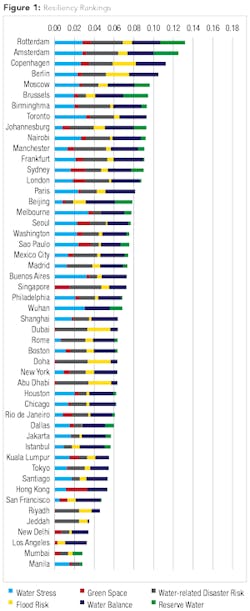

In its measures of resiliency, Arcadis ranked American cities well below the model water management systems in the Netherlands, Denmark, and Germany, in their preparedness to meet water-related challenges (see Fig. 1). Washington, D.C., was the highest-ranking U.S. city but it came in 19th on the overall list. The nation’s capital got low scores for “water stress,” the percentage of available freshwater used locally; the percentage of the city covered in green space; the number of floods the city experienced since 1985; and the capacity of its reservoirs within 100 kilometers (about 62 miles) of the city.

Philadelphia ranked 25th on the resilience list, while Los Angeles - with its lack of green space and its continuous rainfall deficits working against it - sank to the bottom at 48th place. The rest of the American cities rest in the lower half of the list of 50.

“We have some work to do,” said Edgar Westerhof, flood risk and resilience lead at Arcadis. “There are some factors that we need to take into account, like climate change, that make our coastal cities more vulnerable. Overall, it seems that European cities are not faced with some of the extreme weather conditions that U.S. cities are.”

One of the issues that puts American cities in peril, Westerhof noted, is the nation’s aging water infrastructure. Low-lying and exposed facilities like sewage treatment plants do not have the capacity or strength to deal with the severity of today’s storms. “Looking at waterfronts along the Sandy-affected area, they were fully exposed to any event that would happen,” said Westerhof. “A severe storm can cause a backflow, and this shows that the system is not sufficient to deal with these challenges.”

It’s not that U.S. cities have been unaware of the risks coming their way, said Westerhof, but action tends to come out of crisis - and so far, some of the cities examined in the report have not had to endure a significant emergency. “Along the east coast and places in the west, there can be a fear of legal or regulatory complexities,” he said. “It has to do with collaboration as well, and how stakeholders are capable of finding each other. Where do you share a mutual concern? That’s where you can find each other.”

A native of the Netherlands, Westerhof has seen the positive results of collaboration between public utilities, private industry and community leaders to maintain the world’s most effective water management system. “In the Netherlands, there’s a culture of working together,” he said. “We all know these capital-intense projects will last a long time, but speeding up procedures based on mutual trust - that is the key.”

If cities can find a way to involve private industry and invest in achieving resilience, Westerhof said, the pace moves more quickly. “You need a business case to accelerate resilience,” he said. “Wherever you are in the world, funding is always limited, but if you step up and have the private sector participate as well in public-private partnerships, all the better.”

The Norfolk Partnership

Norfolk, Va., has chosen to lead by example, making water one of the primary issues in its strategy to address overall resilience. “We’re working with our partners, our major assets, and our sister cities to understand what it will take to be a vibrant economy as the sea level rises,” said Christine Morris, Norfolk’s chief resilience officer.

Walloped with a hurricane in 2003 and a nor’easter in 2009, the coastal city of Norfolk saw the need to protect its residents from destruction of their homes and property, and from potential loss of life. “In a series of storms, we were seeing water in new places on a regular basis,” said Morris. “Heavier downpours and the resulting collection of water was more than our systems could handle.”

Working with Dutch representatives to fully understand the area’s water system, the Norfolk team went through historic maps to see what changes had taken place in the area’s water system over time. “It was a real eye-opener for me - I understood how you can use that history to manage water going forward,” Morris said. “Our thinking evolved very quickly. Now we are looking to hold the water as far up in the watershed as we can - managing it away from the spaces where it floods. Hold it, slow it, try to clean it, and when we can, release it into the existing system.”

In addition, in February 2016, the city of Norfolk and USACE signed the Feasibility Coast Share Agreement, allowing the Norfolk District Corps of Engineers to take a comprehensive look at the city to identify areas in which projects could be constructed to protect it from sea-level rise.

“I always say that cities change continuously - physically, demographically, and economically,” said Morris. “If water is going to be in places that it wasn’t before, how do you take that opportunity and make it into something great? Having more water is not necessarily a terrible thing if you use it in ways that enhance the life of the city.”

About the Author: Randi Minetor is a freelance writer based in Rochester, N.Y.

Resources for Resilience Planning

Not every city has the resources that New York has, but there are other tools and assistance that any municipality can access.

One of the challenges smaller utilities face is that at the worst possible time - when an emergency situation is in progress - the staff finds itself underequipped to handle the problem. To address this issue, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has introduced its Water/Wastewater All-Hazard Boot Camp Training, a comprehensive computer-based course for water and wastewater employees. The course incorporates emergency planning, response, and recovery activities, including: identifying and funding potential hazard mitigation projects, developing an Emergency Response Plan, coordinating mutual aid and assistance, conducting damage assessments, and many more. Learn more at www.epa.gov/waterresiliencetraining/waterwastewater-utility-all-hazards-bootcamp-training.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) Institute for Water Resources (IWR) has a Flood Risk Management program that can provide information and guidance to municipalities, including floodplain information, assessment of potential climate change impacts, and project planning and implementation. Information is available at www.iwr.usace.army.mil/Missions/FloodRiskManagement/FloodRiskManagementProgram.aspx.

USACE also has resources to help communities manage their water in environments susceptible to drought. To learn more, visit www.corpsclimate.us/docs/USACE_Drought_Contingency_Planning_in_the_Context_of_Climate_Change_SEPT_2015.pdf.

USACE and the Federal Emergency Management Association (FEMA) co-chair the Federal Interagency Floodplain Management Task Force, which seeks to promote and encourage floodplain management decisions to reduce loss of life and property. Its reports and recommendations are available online at www.fema.gov/federal-interagency-floodplain-management-task-force.

More WaterWorld Current Issue Articles

More WaterWorld Archives Issue Articles