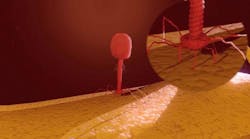

The bacteriophage T7NLC is a virus that can find the bacteria E. coli in water. The bacteriophage can bind to the E. coli and it shoots its own DNA into the bacteria. It then lyses breaks open the bacterium, releasing an enzyme that destroys it, as well as sending out additional phages to attack other E. coli. Image: Sam Nugen/Cornell University.

ITHACA, NY, OCT 15, 2018 -- To rapidly detect the presence of E. coli in drinking water, Cornell University food scientists now can employ a bacteriophage - -a genetically engineered virus -- in a test used in hard-to-reach areas around the world.

Rather than sending water samples to laboratories and waiting days for results, this new test can be administered locally to obtain answers within hours, according to new research published by The Royal Society of Chemistry, August 2018.

"Drinking water contaminated with E. coli is a major public health concern," said Sam Nugen, Ph.D., Cornell associate professor of food science. "These phages can detect their host bacteria in sensitive situations, which means we can provide low-cost bacteria detection assays for field use - like food safety, animal health, bio-threat detection and medical diagnostics."

The bacteriophage T7NLC carries a gene for an enzyme NLuc luciferase, similar to the protein that gives fireflies radiance. The luciferase is fused to a carbohydrate (sugar) binder, so that when the bacteriophage finds the E. coli in water, an infection starts, and the fusion enzyme is made. When released, the enzyme sticks to cellulose fibers and begins to luminesce.

After the bacteriophage binds to the E. coli, the phage shoots its DNA into the bacteria. "That is the beginning of the end for the E. coli," said Nugen. The bacteriophage then lyses (breaks open) the bacterium, releasing the enzyme as well as additional phages to attack other E. coli.

Said Nugen: "This bacteriophage detects an indicator. If the test determines the presence of E. coli, then you should not be drinking the water, because it indicates possible fecal contamination."

First author Troy Hinkley, a Cornell doctoral candidate in the field of food science, is working as an intern with Intellectual Ventures/Global Good, a group that focuses on philanthropic, humanitarian scientific research, to further develop this bacteriophage.

Describing the importance of phage-based detection technology, Hinkley said, "Global Good invents and implements technologies to improve the lives of people in the developing world. Unfortunately, improper sanitation of drinking water leads to a large number of preventable diseases worldwide.

"Phage-based detection technologies have the potential to rapidly determine if a water source is safe to drink, a result that serves to immediately improve the quality of life of those in the community through the prevention of disease," he said.