By Sarah Fister Gale

Water security is a global issue and even in the United States, with our rich and diverse water resources, once relied-upon water systems are now at risk. California is slowly recovering from a five-year drought, the Colorado River is beginning to run dry in places, and Lake Mead, which supplies water to 22 million people, reached record low levels in 2016 and could run dry by 2021 if conditions persist. And the problem isn’t limited to the arid southwest. Water shortages are expected in 40 states over the next decade, according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

These trends are driving many communities to make alternative water projects a key component of their water diversification efforts, according Jonathan Loveland, alternative water supply practice leader for global engineering procurement and construction firm Black & Veatch in Irvine, Calif. “Projects to treat alternative sources of water have become common in states like Florida, California, and Oklahoma, which are all facing significant water shortages,” he said. “All of their easily-treated water has been utilized, so they need to turn to alternative sources.”

Beyond the Basin

Even in the water-soaked northeast, rapid urban development is forcing some communities to import clean water at significant expense to meet the needs of their growing populations. “It’s the first time we are seeing ‘wet states’ face water shortages,” said Kathryn Henderson, research manager for the Water Research Foundation (Denver, Colo.). Atlanta, for example, is currently pursuing a $300 million project to dig a five-mile tunnel from the Chattahoochee River to fill an abandoned quarry with 2.5 billion gallons of water. “The project will expand the city’s back-up water supply from three days to 30,” she explained.

And in eastern Virginia, the Hampton Roads Sanitation District (HRSD) has launched its Sustainable Water Initiative for Tomorrow (SWIFT), an indirect potable reuse project that involves treating wastewater to drinking water quality standards then injecting it into the Potomac aquifer, which is the size of a Great Lake and serves multiple states in the east coast region.

With the rapid depletion of traditional water sources, such projects are becoming commonplace as communities seek to diversify their water assets and build resiliency against climate change and water risks. “It requires a paradigm shift for communities to start thinking about all of their water as a resource,” Henderson said. This is the idea behind the “One Water Movement,” which is an integrated approach to managing finite water resources that views all water - including wastewater, stormwater, graywater and seawater - as resources that can be sustainably managed. WRF recently released the Blueprint for One Water to help communities manage water resources more holistically. “It outlines the steps you need to develop a plan for being more innovative and breaking down the barriers between water and wastewater,” she noted.

While news of water shortages is concerning, it has had the positive effect of making the public more open to alternative use projects, said Allen Carlisle, CEO of Padre Dam Municipal Water District in California. “People understand that there is no new water on the planet,” he said.

His community draws most of its drinking water from the Colorado River, which has hundreds of discharge points upstream from the dam. “We are already drinking recycled water,” he noted. So, his team decided they should get into the recycling business.

But Can We Afford It?

Padre Dam is in the midst of planning the East County Advanced Water Purification Program to develop a new, reliable, locally-controlled, drought-proof drinking water supply in partnership with Helix Water District, the City of El Cajon and San Diego County. San Diego’s East County currently imports 100 percent of its water, and collects four million gallons of wastewater per day. Half of that wastewater is treated for purple pipe irrigation for the community, and half is sent 20 miles to a facility in San Diego for treatment, which the community pays for.

Carlisle’s team realized they were throwing away a valuable resource. “The technology exists to treat wastewater to drinking water standards,” he pointed out. The question was: could the community afford to build it?

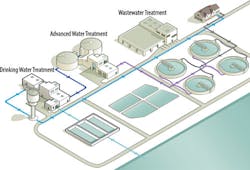

Padre Dam already has a wastewater treatment facility to treat wastewater for irrigation, so the basic infrastructure is in place. But the project includes expanding its capacity and updating the treatment system with additional purification steps that will ultimately bring water quality to near distilled standards. That water will then be discharged into the local groundwater basin.

Even though the water quality would be sufficient for direct potable reuse (DPR), the state has no regulations governing it, so they chose to move forward with an indirect system, he explained. Once completed in 2035, the system will provide 30 percent of the community’s drinking water and eliminate the cost of shipping wastewater to the San Diego plant.

It’s a bold vision, and the total cost of achieving it is $509 million dollars. “I worry less about whether we can clean the water, and a lot more about the economics of it,” he said.

Carlisle’s team has been working with a number of agencies to stitch together a tapestry of funding sources, and so far it’s looking good. Between local partnerships, their capital projects budget, grants from the California Department of Water Resources, State Revolving Fund loans, and money from the federal Title 16 program, which supports water reclamation efforts, they feel confident that they can make the project work.

“We are feeling pretty good on the financial side right now,” he said. However, the facility also has to be cost-effective once it’s built. If all continues according to plan, they expect to spend $1,900 per acre-foot of water by the time the system goes online. That’s $300 more per acre-foot than they spend to purchase water today, but given the expected increase in future imported water costs, the discrepancy won’t last long.

Finding this economic balance is the key to any successful alternative water supply project, Loveland said. “Treating alternative water sources is always going to be more expensive than traditional water treatment, so you have to balance availability of the resource with that cost.”

As more communities demonstrate the viability of these projects, and regulators provide clear guidance on what is allowed in terms of potable reuse, these projects will likely become more mainstream and potentially more affordable. “The technology and the science are there,” said Henderson. “Now it’s mostly economic barriers that we need to address.”

She believes the next decade will bring many new treatment options to market that will make it easier and more efficient to treat alternative water sources. In the meantime, because these projects can take a decade or more to get up and running, communities with growing concerns about water shortages should start thinking now about how they are going to address these issues in the future.

As they evaluate their options, they might consider visiting cities that have implemented different types of alternative water projects to see what’s possible, and meet with regulators and health department officials to be sure any projects they pursue meet local and state requirements. “Getting local officials on board early on is critical,” said Henderson. “The more involved they are in your project plan, the better.”

About the Author: Sarah Fister Gale is a Chicago-based correspondent for WaterWorld. Over the last 15 years, she has researched and written dozens of articles on water management trends, wastewater treatment systems and the impact of water scarcity on businesses and municipalities around the world.