Affordability programs may become more common as rising infrastructure costs, extreme weather, and water quality challenges force water and wastewater utilities to raise rates higher and more frequently.

By Katie Cromwell, Kevin Kostiuk, and Henrietta Locklear

Both joy and frustration are evident in the tiny customer service stations at a large water utility. The utility is rolling out a new affordability program — its latest attempt to balance the needs of the people it serves while urgently looking to fund the infrastructure replacement program it must implement. A significant percentage of residents in this city live in poverty. Here, bills are frequently paid in person, delinquency rates are high, and applications to receive assistance are more often handled directly with a utility staff person than they are online. Customers express the frustration of juggling which bills they will pay in any given month, and any help from an assistance program is met with relief.

It’s a scene that may become more common as rising infrastructure costs, extreme weather, and water quality challenges force water and wastewater utilities to raise rates higher and more frequently. While some customers struggle to pay, the utilities wrestle with their own long-term financial sustainability.

Affordability is a pressing challenge. This four-part series will review the landscape of water affordability programs, explore what other industries are doing and the lessons they’ve learned in the process, and discuss the near future of affordability programs.

How Did We Get Here?

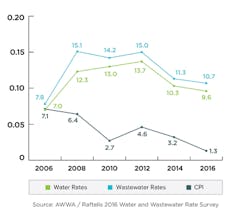

Over the last decade, water and sewer costs have increased significantly and consistently, outpacing the consumer price index (see Fig. 1). There are several drivers, but almost universally, utilities have historically not charged customers for the full cost of providing service, leaving infrastructure investment underfunded. This was possible because in the past federal grants funded water and wastewater infrastructure, and developers contributed large investments to support system growth.

Figure 1. Rate increases vs. CPI increases over the last decade

Federal grant funding is nearly nonexistent now as the need for repair, replacement, and expansion has increased. Politics come into play here, as municipal utilities with elected boards and councils face difficult choices about raising rates or borrowing funding. The process of raising rates to provide funding for water and wastewater infrastructure, which largely goes unseen, faces opposition from ratepayers.

Extreme weather also plays a role. Increasing frequency, intensity, and duration of severe weather events have created source-water availability challenges in some communities and combined sewer overflows and flooding in others. Building resiliency and responding to natural disasters requires additional long-term funding and more rate increases.

Water quality is increasingly in the spotlight, forcing additional investments driven by regulation. The plight of Flint, Mich., was a rallying cry for many water quality and affordability advocates. A combination of a shrinking rate base, economic hardship in the community, and political and management issues created a perfect storm where the health of city residents were put at risk because of a lack of investment.

In addition to high-profile issues like lead, wastewater contaminants of concern such as hexavalent chromium, pharmaceutical compounds and personal care product elements are driving the need to invest in additional water treatment capabilities. On the wastewater side, investments in phosphorus removal to meet regulatory discharge requirements are growing alongside energy costs. These regulatory burdens on water systems will continue to increase, requiring new infrastructure for treatment, testing, and monitoring, and ultimately, additional revenues from ratepayers.

How Do We Define Affordability?

Affordability is defined by the individual, not the utility. As such, the water industry struggles with a definition. While commonly defined as the ability of individual customers to pay for water and wastewater services that are adequate to meet their basic needs while maintaining the ability to pay for other essential costs, the key is that affordability must be evaluated at the individual customer level. Determining what is actually affordable for each individual customer is difficult to do, yet when faced with approving rate increases city councils and boards almost always ask, “Is this affordable?”

More than two decades ago, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) published the guidance document, Combined Sewer Overflows – Guidance for Financial Capability Assessment and Schedule Development. Although it was intended as a planning tool to evaluate the financial resources at the utility level associated with funding a Combined Sewer Overflow Long-Term Control Plan (CSO LTCP), this document has more broadly been used as the basis for financial capability measurement across the water and wastewater utility industry.

It proposed two main indicators for evaluating financial capability: a community financial strength indicator and a customer burden indicator. In the absence of other guidance, utilities have focused on the customer burden indicator and used it as a proxy for measuring affordability.

The EPA’s customer burden indicator is measured as the cost of water and/or wastewater service divided by the median household income (MHI). The guidance document indicated that water or wastewater costs that exceed 2 percent of MHI, or 4 percent of MHI for a combined water and wastewater bill, would exert a high burden on customers. This percent of MHI standard has become the common water and wastewater affordability standard used today.

But this 2 percent of MHI was not intended to be applied and used as a measure of affordability at the customer level. Recognizing this as a concern, EPA has regularly indicated that this was not the intent and is currently considering how to provide additional guidance that pertains to a customer level. In addition, other flaws in using the percent of MHI standard for addressing customer level affordability include its use of average consumption rather than basic water needs, its failure to consider costs of other essential goods, and its use of median income rather than low income.

With the understanding that using the percent of MHI proxy has shortcomings, several other affordability metrics have emerged. These methods focus on individual customers, accounting for essential non-utility costs, and concentrate on low-income residents, utilities’ most financially vulnerable customers.

Affordability Ratio – The affordability ratio is the ratio of basic water and wastewater services to disposable household income. The disposable household income can be calculated using median household income, poverty level income, or 20th percentile income. The affordability ratio addresses many of the weaknesses of the 2 percent MHI, but the ease of calculation depends heavily on the availability of household-level data.1

Percentage of Poverty Level Income – The U.S. Census Bureau calculates poverty thresholds that are meant to reflect the minimal cost of living at varying household sizes. Using an assumed household size, the cost of basic water and wastewater services can be calculated as a percentage of poverty level income. This affordability metric has the benefit of being sensitive to the costs of essential goods and services and focuses on low-income customers. However, this metric does not reflect regional variations in cost of living since the poverty thresholds are calculated on a national scale.

Minimum Wage Hours – Using minimum wage hours as an alternative affordability metric has the benefit of being easy to understand, simple to calculate, and provides valuable insight into the impact of water and wastewater bills on low-income customers. The U.S. federal minimum wage or state or local minimum wage could be used for this analysis. Additionally, this analysis can be scaled based on household size.

Some utilities, including the City of Phoenix, Ariz. and the Borrego Water District (Calif.), have used these alternative affordability metrics to measure the impact of their rates.

Limitations on Water Affordability Programs

In response to concerns about affordability, many utilities are seeking to enhance customer assistance programs, provide funding to customers to make water bills more affordable, or build affordability measures directly into their rate structures. Funding for these programs can be challenging because of legal restrictions at the state and local level. Some states strictly limit funding options for affordability programs, while others are ambiguous or explicitly allow only certain funding sources.

Building affordability into rate structures can also be challenging where legislation strictly defines cost of service rates and precludes rate structures that provide subsidization. Currently, most water utilities that have affordability programs utilize rate-revenue-generated funds, foundation or grant funds, or other voluntary programs to collect money used for affordability programs. Utilities without the ability to provide direct funding are left with making policy changes to allow for payment arrangements, reducing delinquency fees, and implementing conservation programs to get at this issue within these constraints.

The concerns and challenges of affordability are not isolated to one type of water and wastewater utility. From coast to coast, small to large, rural, suburban, and urban, utilities are focusing on their most vulnerable customers. Two examples that illustrate the range of utilities addressing affordability are City of Thousand Oaks, Calif., and the Philadelphia Water Department.

City of Thousand Oaks, Calif.

Water safety and affordability legislation is working its way through California’s legislature. The proposed legislation would fund direct assistance to disadvantaged communities and water systems dealing with legacy issues from agricultural pollution to raw water sources. However, there are constraints on California public water and sewer service providers’ ability to help. Constitutionally, agencies cannot use revenues from rates to subsidize other users (California’s Proposition 218 requires strict cost of service adherence). Only non-rate revenues are available to promote affordability or fund affordability programs.

In 2017, the City of Thousand Oaks adopted a program that relies on the requirements of regional investor-owned gas and electric utilities’ California Alternate Rates for Energy (CARE) program to determine eligibility based on household income and persons per household or enrollment in public assistance programs including SNAP, WIC, and Medicaid. The city, which has 16,000 water accounts and 38,000 wastewater accounts, is using non-rate revenues including late and non-payment fees to fund its program. Funding for 2018 is $100,000 each for the water and wastewater utilities and provides $5 and $10 per month credits to enrolled customers’ wastewater and water bills, respectively.

The city estimates it can cover 1,600 wastewater customers and 800 water customers in the program. An average customer pays around $113 per month for water and $29 per month for wastewater. Enrollment in the program for both services will provide a 10 percent discount to the customer.

Philadelphia Water Department

The Philadelphia Water Department is one of the largest utilities in the nation, providing water service to 1.7 million people in its service area. With a poverty rate over 25 percent, it is one of the most economically challenged cities in the country. In 2017, the Philadelphia Water Department implemented a uniform application for customer assistance programs, for both its existing program and its newly established Tiered Assistance Program (TAP).

Customers apply for program participation, and TAP aids income-eligible customers through fixed monthly bills that are based on household income. The program is available to customers with household income at or below 150 percent of federal poverty level, and customers with special hardships at any income. Approved program participants receive monthly bills that range from 2 to 4 percent of their household income.

Next in the Affordability Series

As the focus on water affordability intensifies, utilities are looking for solutions for their customers while they continue to provide safe, clean water and maintain financial sustainability. Compared with the water utility industry, other industries have a much more mature affordability landscape. Many other industries, particularly gas and electric utilities, have dealt with similar affordability issues. Part two of this series will discuss some best practices and lessons learned from other industries and their applicability to the water utility industry. WW

=> Read Part 2: Affordability in Other Industries

=> Read Part 3: Affordability: Lessons Learned from Gas and Electric Utilities

=> Read Part 4: The Future of Water Affordability Programs

About the Authors:

Katie Cromwell is a senior consultant with Raftelis in its Cary, N.C., office. With a background in environmental regulation, permitting and compliance as well as financial management, she has worked extensively with water, wastewater, and stormwater utilities on implementing funding strategies including the analysis and visualization of affordability within communities.

Kevin Kostiuk is a senior consultant with Raftelis in its Los Angeles, Calif., office. His background is in economics and accounting and his areas of expertise include financial accounting, environmental policy, water supply and flood control policy and operations. In addition he has worked extensively in innovative rate design in response to emerging issues such as drought and affordability concerns.

Henrietta Locklear is a senior manager with Raftelis and leads its Memphis, Tenn., office. Her background is in local government management including environmental finance and public policy. Her work includes assessing and implementing affordability programs for large utilities. She leads the Raftelis affordability community of practice, a group of practitioners within the company engaged in leadership on affordability issues in the utility industry.

REFERENCES

1. Teodoro, Manuel. Measuring Household Affordability for Water and Sewer Utilities. Journal AWWA, January 2018.110.1.http://mannyteodoro.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Teodoro-JAWWA-2018-affordability-methology.pdf

Circle No. 238 on Reader Service Card