Affordability in Other Industries

In part two of our four-part affordability series, we examine the affordability landscape in our sister industry – energy utilities

By Katie Cromwell, Kevin Kostiuk, and Henrietta Locklear

Water and wastewater utilities are being forced to adopt significant rate increases to pay for necessary capital improvements and increasingly expensive sources of supply. These increases have a disproportionate impact on the ability of low-income customers to afford their bills.

=> Read Part 1: Affordability Meets Sustainability

While affordability is a fairly recent concern for the water industry, it has been a major challenge for the energy sector for decades. The 1970s energy crisis arrived on top of a recession. Baby boomers can recall, every day it seemed like their money was worth less and less. Gasoline was rationed and unemployment soared. People turned to burning wood at home to keep warm instead of turning on the heat and President Carter urged Americans to turn down the thermostat and put on a sweater. The universal nature of energy affordability became a national issue and precipitated federal action.

Out of that tumultuous time of inflation and oil shocks, the country’s energy affordability policy was born. In 1980, the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) was established and the federal government began funding assistance to low-income residential customers struggling to pay for gas and electric heating. Later, the program expanded to include cooling bills. LIHEAP recognized both the high cost of heating and cooling and the reduced purchasing power of consumers through soaring inflation.1

In fiscal year 2017, the congressional budget for LIHEAP was $3.1 billion, most of which went to provide assistance for energy bills.2 Households are eligible for LIHEAP if their income is 150 percent or less of the federal poverty level. Recent Health and Human Services (HHS) data shows that of an estimated 35 million eligible households, 21 percent received assistance for heating, cooling, and winter crises.3 Today, 42 percent of American households are designated as low income, and for these households the average energy bill consumes 8.2 percent of income.4 While the amount and coverage fall far short of the need for assistance according to advocates5, it is in stark contrast with the assistance landscape of water utilities, where there is no federal policy, program, or budget to assist customers with their water, wastewater, and stormwater bills.

Energy Affordability Landscape

Although LIHEAP is a federal program, it is administered at the state or tribal level through block grants from Congress. Individual grantees then administer their own programs and distribute monies to individual enrollees. States with extreme temperatures resulting in high heating or cooling costs may also appropriate additional state funding to the program.

Created around the same time and impacted by the same drivers as LIHEAP, the Department of Energy (DOE) created the Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP). It focuses on improving energy efficiency in homes, providing customers with a home audit to identify areas for weatherization and cost-effective efficiency upgrades. Contractors then make the recommended weatherization updates up to an allotted amount. WAP maintains the same eligibility requirements as LIHEAP, and customers enrolled in LIHEAP are automatically enrolled in WAP.

Together, LIHEAP and WAP provide customers with a combination of short-term direct relief in the form of bill reductions and long-term indirect relief through reduced energy consumption.

In addition, utilities have implemented their own affordability programs that supplement LIHEAP emergency assistance. These programs have frequently been required by state public service commissions that regulate energy utility rate adjustments. In California, for example, Public Utilities Code Section 739.1 requires the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) to assist energy utility customers with household incomes that are at or below 200 percent of the federal poverty level.

Structure of Gas and Electric Affordability Programs

The structure of most gas and electric affordability programs can be broken down into one of three types: 1) flat dollar per month bill reduction, 2) percentage bill reduction, and 3) billing based on customer burden. Each has its own merits, including broadness of coverage, cost, and complexity in design, implementation, and administration.

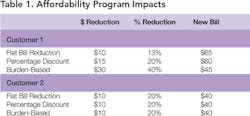

Comparative Example of Hypothetical Affordability Program

ABC Electric Company is deciding between three different affordability programs. Customers with income levels at 150 percent or less than the federal poverty level, by household size, are eligible for the program. ABC Electric Company’s rate structure has a $10 base charge. The three programs that ABC Electric Company are considering are:

• Flat bill reduction program — A $10 base charge discount

• Percentage discount program — A 20 percent reduction of total bill

• Burden-based program — Customers below the poverty level receive a 40 percent reduction; customers between 100 percent and 150 percent of poverty level receive a 20 percent reduction

Customer 1 is a family of four with household income of $20,000 per year and average bill of $75 per month. Customer 2 is a family of two with household income of $24,000 and average bill of $50 per month. Customer 1 falls below the federal poverty level and Customer 2 falls between 100 percent and 150 percent. Table 1 shows the impacts of the different affordability programs on these two customers.

Customer 1 receives the most assistance from the burden-based affordability program, while Customer 2 receives equal benefit under all of the programs. Because Customer 1 has a higher bill, they receive less percentage benefit than Customer 2 under the flat bill reduction scenario despite Customer 1 having more need for assistance than Customer 2.

Other considerations for gas and electric affordability program design include whether to have a fixed or flexible program budget and managing arrearage. Low-income customers may carry balances on their accounts due to missed payments and/or late fees. Having a way for customers to pay down arrears is considered a valuable component in an affordability program. Arrearage management may include forgiving some portion of past due balances for every bill paid while enrolled in the program.

State-Level Example

The California Alternate Rates for Energy (CARE) program is a percentage discount program providing a 30 to 35 percent discount on electricity and 20 percent discount on natural gas bills. Eligibility is capped at 200 percent of the federal poverty level by household size (currently $32,990 for a 2-person household or $50,200 for a 4-person household in California). The program is offered to customers of utilities governed by the state Public Utilities Commission (PUC). Customers may also be eligible for the program if they are enrolled in other national programs including Medicaid, Food Stamps/SNAP, and LIHEAP, among others.

Similar to CARE, the Family Electric Rate Assistance (FERA) program uses a 250 percent federal poverty level eligibility cap. It is available to customers of the big three investor-owned electric utilities in the state: Southern California Edison (SCE), Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E), and San Diego Gas and Electric (SDG&E). FERA applies a 12 percent discount to electric bills, which covers a portion of low-income households that exceed the eligibility thresholds for CARE.

Funding Sources for Gas and Electric Affordability Programs

Bill reduction is the largest expense of an affordability program. When evaluating program funding, utilities must decide whether to fix the program budget or allow the budget to vary with enrollment.

Utilities with fixed budget programs limit funding required by ratepayers; however, participation in the program may be restrained to stay within budget. As a result, some otherwise eligible low-income customers may not benefit, or benefit fully, from the program. Affordability programs with flexible budgets do not restrict enrollment so the level of revenue required from other customers will vary.

Gas and electric utility program funding is typically collected through base rates or through a form of rider. If the revenue for the affordability program is collected through base rates, then the costs will be reviewed in rate case proceedings. Riders on utility rates are often subject to an annual true-up to allow the utility to collect revenue that matches the needs of the program.

Rate riders work particularly well in cases where there is a flexible affordability program budget. Regardless of whether a utility funds the affordability program through base rates or rate riders, the costs are typically spread across all rate classes. Some utilities fund all or a portion of the program through voluntary contributions from ratepayers. However, in our discussions with program administrators only a minority of customers choose to make voluntary contributions.

Comparison with Water Industry Affordability

The consequences of economic uncertainty and the energy crisis during the late 1970s triggered swift action at the national level to address energy affordability. As a result, energy affordability programs have had a decades-long head start on water affordability programs.

Unlike water utilities, most energy utilities are regulated by state-level public service commissions rather than local boards. State regulation means that more consistent requirements for affordability programs are implemented within energy utilities in the same states.

Many water utilities have experienced their own affordability-related issues but the majority of these issues have been at the regional and local level and have not necessarily coincided with large-scale economic downturns. The impetus for national-level action to deal with water affordability has simply not occurred like it did for the energy utilities, leaving a patchwork of differing levels of water affordability programs across the country. Some states even prohibit water rate revenues from being used for assistance programs. A recent Brookings Institution blog post suggests that implementation of a national policy and federal funding program similar to LIHEAP would be a powerful component of a solution to water affordability.6

Next in the Affordability Series

Part three of this series will focus on what lessons and best practices from the gas and electric industry could be applied to the water utility industry. WW

=> Read Part 3: Affordability: Lessons Learned from Gas and Electric Utilities

=> Read Part 4: The Future of Water Affordability Programs

About the Authors:

Katie Cromwell is a senior consultant with Raftelis in its Cary, N.C. office. With a background in environmental regulation, permitting and compliance as well as financial management, she has worked extensively with water, wastewater, and stormwater utilities on implementing funding strategies including the analysis and visualization of affordability within communities.

Kevin Kostiuk is a senior consultant with Raftelis in its Los Angeles, Calif., office. His background is in economics and accounting and his areas of expertise include financial accounting, environmental policy, water supply and flood control policy and operations. In addition, he has worked extensively in innovative rate design in response to emerging issues such as drought and affordability concerns.

Henrietta Locklear is a senior manager with Raftelis and leads its Memphis, Tenn., office. Her background is in local government management including environmental finance and public policy. Her work includes assessing and implementing affordability programs for large utilities. She leads the Raftelis affordability community of practice, a group of practitioners within the company engaged in leadership on affordability issues in the utility industry.

References

1. “Energy Crises of the 1970s,” Smithsonian Institution (online), http://americanhistory.si.edu/powering/past/history3.htm.

2. “LIHEAP and WAP Funding,” LIHEAP Clearinghouse, National Center for Appropriate Technology (online), https://liheapch.acf.hhs.gov/Funding/funding.htm.

3. Perl, Libby. “LIHEAP: Program and Funding,” Congressional Research Service (online), http://neada.org/wp-content/

uploads/2013/08/CRSLIHEAPProgramRL318651.pdf, July 2013.

4. Coggin, John. “3 New Tools for Advancing Energy Affordability in Low Income Communities,” Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy (online), https://www.energy.gov/eere/

articles/3-new-tools-advancing-energy-affordability-low-

income-communities, January 2018.

5. Campaign for Home Energy Assistance, https://www.liheap.org/.

6. Kane, Joseph. “Water affordability is not just a local challenge but a federal one too,” The Brookings Institution (online), https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2018/01/25/water-affordability-is-not-just-a-local-challenge-but-a-federal-one-too/, January 2018.

Circle No. 242 on Reader Service Card