By Kelsey Beveridge

One Water management seeks to maximize water resources, break down barriers within the water sector, and form partnerships with other sectors

Traditionally, the planning and water management sectors have tended to collaborate solely within their own communities. It is important to bridge the disconnect between planners and water resource managers not just within a given community but also across communities. Incorporating new approaches across sectors can increase resiliency in a community, add value to water systems, and create economic and social health for communities. Unfortunately, the mechanisms to integrate land use planning, urban planning, and comprehensive planning considerations into water resource activities are not well defined. Nonetheless, while there are barriers to coordinating across both sectors, there are effective ways to link up planners and water resource managers.

Two projects by The Water Research Foundation examined opportunities for collaboration of planning and water resource management. Joining-Up Urban Water Management with Urban Planning and Design1 identified existing urban planning processes that connect water resource planning with management and bridge the disconnect between urban planners and water resource managers. Integrating Land Use and Water Resources: Planning to Support Water Supply Diversification2 evaluated water supply diversification efforts through an integrated approach and developed resources that help advance collaborative water and land use planning.

There are a variety of strategies that can be used to meet the water supply needs of communities and municipalities. These methods include potable reuse, conservation, non-potable reuse, stormwater capture, rainwater capture, and desalination, among others. Often, non-traditional water supplies are not managed by the water provider but are installed independently and often without involving a broader monitoring entity. The coordination in communities among water managers and planners varies, but a greater level of coordination can improve the sustainability of the overall water supply and diversify the portfolio.

Photo: dbaumann/Pixabay

Both projects studied the successful collaboration efforts of Tucson Water, which services Pima County, Ariz., and has a service area of approximately 713,000 people and 9,200 square miles. The dry climate, changing weather patterns, population growth, and water supply are key considerations for future planning. While there is room for improvement in future projects, there have been successful instances of collaboration for immediate needs. The most common examples involve water supply and wastewater, conservation and environmental protection, and floodplain management. When collaboration has been successful between planners and water professionals, supportive political and social conditions were enabling factors.

In Stoker et al., a specific instance of successful collaboration around a Commercial Rainwater Harvesting Ordinance was examined, including drivers for water managers and planners to work together and factors that enabled them to collaborate. Success factors included regular stakeholder meetings and workshops to fill educational gaps. This led to a new standard for commercial properties to use rainwater for irrigation and support the city’s water conservation efforts.

Fedak et al. looked broadly at collaboration efforts for alternative water supply planning. This included rainwater harvesting, but also reclaimed water for new developments and recharging aquifers with treated effluent as part of the Central Arizona Project. Several key factors led to successful integration solutions, such as a multi-jurisdictional working group, trust and ongoing coordination between city and county agencies and departments, and public education and stakeholder engagement to address community concerns. These efforts led to green infrastructure resolutions, guidelines, regulations, rebate programs, and planning tools.

There are incentives to an integrated, coordinated plan, including improved reliability and resilience, environmental protection, improved water management, and supply sustainability. Both projects recognized an opportunity to facilitate collaboration in order to improve allocation of resources. Fedak et al. identified how different types of communities and municipalities weigh drivers against their priorities when implementing alternative water supplies. The project outlines issues in need of greater water and land use collaboration, how to identify coordination issues, common barriers, and tactics to overcome barriers. Stoker et al. had a similar premise that identified collaboration factors localities can use to join policies that promote One Water solutions in the context of urban development, such as urban zoning and development patterns to improve long-term resiliency.

Survey Results

The two projects conducted a joint survey that engaged a large group of water utility and planning professionals. The survey, which built upon a previously conducted survey on water and planning by the American Planning Association, identified issues where planners and water providers need stronger collaboration and sought to understand how planning decisions are made. While there are communities that try to utilize integrated approaches, there are challenges that have limited the scope of collaboration between planners and water resource managers. The main challenge in coordination is the time required to align work products with more people when time is a constraint. In addition, water professionals and planners have different final objectives that make it hard to develop unified plans. However, the research results showed there is a net benefit from coordination despite these challenges.

The survey uncovered several important findings that reflect an overall desire for long-term integrated decision-making. Generally, the results suggest there is more support from planners to have water managers engaged than the other way around, as planners are already more accustomed to engaging multiple stakeholders in their decision-making processes. Additional benefits of coordinated decision-making included reducing competition for limited water supplies, increasing water supply sustainability at reduced costs, providing better information to the public, and increasing predictability of the development process. Because water planning and its related infrastructure investments are long-term processes, there is a good reason to consider these issues within the context of long-range land use planning.

Coordination Tools

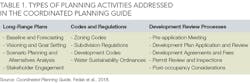

Utilizing the survey results and input from stakeholder interviews, Fedak et al. produced the Coordinated Planning Guide: A How-To Resource for Integrating Alternative Water Supply and Land Use Planning.3 The guide identifies specific opportunities in the water and land use planning processes where better collaboration can occur by taking results from the research report and turning them into a navigable tool. It is organized into three main categories of community planning activities: long-range plans, codes and regulations, and development review processes (see Table 1). In addition to types of planning activities, the guide discusses solutions at different scales: site, utility, and regional. The intent is that both community planners and water professionals will be able to see themselves in case studies and identify key areas where they can take a lead in advancing collaboration.

In addition, the Stoker et al. report includes tools to help planners and water managers work together, such as the Barriers-Bridges Matrix and a step-by-step Self-Assessment Process for integration. The Matrix is an Excel-based tool that practitioners can use to identify water management priorities that would benefit from cross-sector collaboration between water utilities and urban planners, and then help determine specific strategies for those sectors to use to address management priorities. The Self-Assessment Process tool will help communities understand what is impeding combined policies and planning, as well as methods that can be used to overcome these challenges. The research team also developed a Water and Planning Glossary that includes relevant terms in design, planning, and urban water management to increase understanding and communication between urban planners and water managers.

The recommendations show promise for a more integrated One Water approach and an interest from stakeholders to facilitate collaboration. Alternative supply methods can help alleviate water supply shortages and water quality problems across the country. However, support from leadership in both the water and planning departments is needed to ensure effective and deeper coordination. Communities should coordinate long-range plans, review processes, codes, and regulations to advance the development of alternative water supplies and inform additional approaches. WW

About the Author: Kelsey Beveridge is a technical writer at The Water Research Foundation.

References

1. Stoker, P., G. Pivo, C. Howe, V. Elmer, A. Stoicof, J. Kavkewitz, and N. Grigg. Joining-Up Urban Water Management with Urban Planning and Design, The Water Research Foundation, Alexandria, Va., Project No. SIWM5R13, forthcoming

2. Fedak, R., S. Sommer, D. Hannon, D. Beckwith, A. Nuding, and L. Stitzer. Integrating Land Use and Water Resources: Planning to Support Water Supply Diversification, The Water Research Foundation, Project #4623a, Denver, Colo., 2018.

3. Fedak, R., S. Sommer, D. Hannon, R. Sands, D. Beckwith, A. Nuding, and L. Stitzer. Coordinated Planning Guide: A How-To Resource for Integrating Alternative Water Supply and Land Use Planning, The Water Research Foundation, Project #4623b, Denver, Colo., 2018.

Circle No. 292 on Reader Service Card