Desalination + Renewables: A long engagement without the wedding?

Bringing together renewable energy and desalination has been discussed at length without a major breakthrough of a large-scale, independently powered project coming online. Why is this? With Masdar’s desalination trials now finished in Ghantoot, Abu Dhabi, we take a look at global progress on the issue.

The coupling of renewable energy with desalination has understandably created a real buzz. After all, it’s a match that’s meant to be: the desalination market is trying to shift its legacy image of providing water associated with a high energy cost and partnering with cleaner energy is a good way to do so.

Capitalising on this need, a goal has been set for 20 percent of new plants to be powered by renewables between 2020-2025, by the International Desalination Association’s (IDA) Global Clean Water Desalination Alliance.

Renewable tomatoes

To date there have been several small scale trials across the Middle East, Spain and India, bringing together concentrated solar power (CSP) and seawater desalination. The challenge has been to scale up the size of the operation and make it fully independent, without access to grid power as a back up when the sun isn’t shining.

“Available renewable and desalination technologies can be effectively combined to reduce desalination’s carbon footprint in the near term,” says Thomas Altmann, VP of innovation & technology at ACWA Power. “It’s just a question of time before the right project environment is created to run a 24-hour large scale solar powered desalination plant,”.

He references the Sundrop farms case in Port Augusta, Australia that uses CSP to provide electric power and desalinated water, which is used to grow tomatoes.

Although the evolution of battery technology is being seen as pivotal to achieve that 24/7 independent desalination plant, it is also the “more expensive photovoltaic (PV) option”, says Altmann.

“The simplest configuration would be to use PV technology alongside reverse osmosis, as well as to utilize the grid for night supply or as storage,” he adds. “In the latter case, you would need to ensure the PV plant is much larger than you’d need to run just the desalination plant. You can then dispatch the extra energy produced throughout the day to the available grid and the grid would then return that energy to keep the desalination plant running during the evening and night.”

Saudi investment

In early February engineering firm Metito announced it had secured a contract with the King Abdullah Economic City (KAEC) to construct a “seawater desalination plant powered by solar energy”.

Valued at SAR220,404,144 (US$58.7 million), the desalination plant will start with a capacity to produce 30,000 m3/day of drinking water, expandable to 60,000 m3/day. The project is expected to be in development for 24 months, with production slated to start in the first quarter of 2020. A total of 10 international and regional companies competed in the tender.

Fady Juez, managing director of Metito told WWi that the “scope of the work includes a 2 megawatt (MW) solar plant that will be fully designed, procured, installed, commissioned and integrated with the RO system”.

He says that the solar system will be used to operate the plant, with power consumption based on the water demand from KAEC.

It’s important to note that the desalination plant will remain connected to the grid, for backup power, while the solar power will be fed to the major equipment.

Batteries not included

Others believe time is still needed to couple membranes, PV and battery technology together but that the industry is on the cusp of change.

“For me it’s clear: the future of desalination will be with renewables,” says Carlos Cosín, CEO of Almar Water Solutions. “It’s only a matter of time in the Middle East region. In less than five years, battery technology will have developed further and then we can have an independent solar and photovoltaic desalination plant. I have no doubt about that.”

He says that the reduction of the solar tariff to “below 2 cents is amazing” and provides a double opportunity. “First, we can reduce the price of the water and even better is that as a result I think [technology] progression will continue,” he says.

Cosín is referring to the “record tariff” of 1.75 cents/kilowatt hours (kWh) achieved in the tender for the Sakaka project in Saudi Arabia, as well as recent tariffs of 2.5-3 cents/kWh achieved in recent PV tenders across the UAE. Such low tariffs are demonstrating that renewable energy has developed so far that it’s more competitive than conventional energy supply.

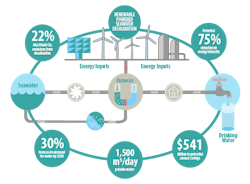

Almar’s CEO believes that the overall reduction of CO2 emissions in plant operation will be a further benefit that “has to be compensated with the tariff” and could lead to a reduction in the amount oil consumed in the Middle East. To provide some context, in Abu Dhabi alone, desalination is estimated to contribute more than 22 percent of the Emirate state’s total CO2 emissions.

Others believe battery storage is not the answer for large scale renewable desalination.

“Battery storage is very expensive in general and the delivery time is quite long,” says Dr Corrado Sommariva, group director at ILF Consulting Engineers. “I do not see them [batteries] as a solution for large SWRO plants for the time being. On the contrary, I would rather see SWRO being modulated (shut down and ramp up) in order to decrease the peak factor and the power load in the grid.”

Renewable water

Hoping to move the needle of desalination energy efficiency is Masdar’s Renewable Energy Water Desalination Programme, for which the results are now in.

As WWi has reported in the past, a total of five small scale plants (Abengoa, SUEZ, Mascara, Trevi Systems and Sidem) all completed the test period of 15-18 months at a site in Ghantoot, located around 65km northeast of the city of Abu Dhabi.

Four of the five plants looked at tweaks to desalination arrangements, including dissolved air floatation and forward osmosis. Meanwhile although Mascara Renewable Water was late to the party, joining the site last, it was the only project to incorporate renewable energy.

For the development, Mascara Renewable Water developed an off-grid, solar powered desalination solution that used a beach well to obtain seawater from a borehole near the sea. The natural sand filtration of the beach well eliminated the need for a dedicated pre-treatment system, according to the company.

A special reverse osmosis (RO) system with a proprietary hydraulic energy accumulator “ensured that the RO system could operate under a varying power supply”. Furthermore, an isobaric energy recovery device (ERD) system recovered energy from the high-pressure brine.

It’s important to note that this plant only operated during sunlight hours – powered by a 30 kWp PV plant.

“The membranes were automatically flushed before sunset to avoid biofouling,” the company says. “A control system managed the continuous operation of the pilot plant under the varying sunlight by adjusting the water production and hence the demand for power throughout the day.”

Following validation at the Ghantoot site, Mascara CEO Marc Vergnet says the company is now developing projects in Mauritius, Cape Verde, South Africa, Morocco and Vanuatu in the Pacific.

Water Innovation Park

One of the overall aims for the Ghantoot projects was to show that current reverse osmosis seawater desalination technologies can achieve an energy consumption of below 3.6 kWh per cubic meter of produced water. All sites passed. Reverse osmosis was also confirmed to be the most “energy efficient desalination technology with 75 percent gains over the current status-quo in the UAE”.

“We are proud to say everyone completed the programme with success,” says Dr Alexander Ritschel, head of application development at Masdar.

Beyond the programme, questions have been asked as to what will happen next at the Ghantoot site? One idea is to keep the facility in operation as a ‘Water Innovation Park’.

Masdar says: “By operating the park at the heart of the region with the world’s largest desalination industry and growing demand, it would lend itself well to ensuring the UAE and Masdar are competitively positioned to develop and commercially deploy novel water technology in the region and beyond for the next 30 years.”

Others believe there could be continued international co-operation at the site.

“Based on the success of the first phase, Masdar plans to continue using the Ghantoot site and expand the portfolio of research activities,” adds Sommariva. “In particular, this will concentrate on the direct coupling of renewables and desalination, as well as dealing with the challenge of brine discharge.”

Ghantoot to one side, Masdar has far wider ambitions in the water market following the experience.

“Our programme was never intended as a R&D project per se,” says Ritschel. “It was intended to become the basis for commercial deployment of these technologies. I think we have accomplishes this task. We are now about to look at how we can use and deploy that technology.”

Masdar’s game plan is to essentially become what is has become for renewables but for water: a project developer and financer. The key thing, according to Ritschel, is that they will “focus on projects that are renewable energy powered desalination plants”.

They intend to join forces with engineering, procurement & construction (EPC) companies to provide small scale solutions for remote locations and islands, in the medium scale – 20,000 – 50,000 m3/day range. “We will always have in mind a zero carbon footprint,” he adds.

Cloud-based innovation

While a healthy dose of patience may be required before the opening of a large scale, independent renewable desalination facility, elsewhere smaller solutions are already hitting the market.

German company Membran-Filtrations-Technik GmbH (MFT) has introduced containerized desalination systems for producing drinking water from either seawater or brackish water.

Called the MFT RO 100 Desalination System, the unit has a capacity of up to 120 litre/hour drinking water and is powered by either 7,5KWp photovoltaic or a 350W Wind turbine, which is stored in lithium-ion batteries.

Pioneering next generation desalination: taken from the Masdar report on Ghantoot

Designed for low-power decentralised applications in remote locations where the energy supply is scarce, the first plant was shipped to a school in La Guajira, Colombia. A remote-control system enables the company to monitor performance real-time from its headquarters in Cologne.

In conclusion, it appears that the engagement between renewables and desalination will continue, without the royal wedding everyone has been waiting for. Yes, solutions such as MFT’s and Mascara’s will continue to provide decentralised desalination solutions on a small scale. Meanwhile, developments of scale – such as KAEC in Saudi Arabia – will continue apace but should be categorised as “part time renewable” – i.e. they are only powered by solar for part of the time. If and when the price of battery storage comes down, then there could be real potential. Until then, patience will be the needed virtue before the opening of the first large scale, independently powered renewable desalination project.

Tom Freyberg is chief editor of WWi magazine.