Reports show that over half of Europe's River Basins will fail to meet the 2015 target of meeting good ecological quality status, required in the Water Framework Directive (WFD). Paul Horton believes we should be looking instead to 2027. Here he provides a personal account and looks at the question of what should really be possible to achieve.

The creditable goals of the Water Framework Directive, adopted in 2000, are under challenge. Why? Europe has an unsustainable water footprint. As Professor Arjen Hoekstra from the University of Twente in the Netherlands, said in an article published in the April-May 2011 edition of WWi, river basins are insufficient as a tool to manage waters. The climate is changing and becoming more variable, with extremes of floods and droughts set to become more common.

Furthermore, rivers in Europe are under "crisis" according to a report published in Nature, which set out the stressor factors of population density, consumption of water, urbanisation, modification of water bodies and pollution. These are at their most acute in Europe, and such findings are backed up by the European Environment Agency's Water assessments 2012. Perhaps even more fundamental than all of these-water does still not sit at the heart of all European policy as it should.

Blueprinting Europe's Water

In November 2012, the European Commission issued the Blueprint to Safegaurd Europe's Water Resources. This document reviewed the current state of Europe's Waters and outlined a series of actions looking at better implementation of current water legislation, proper integration of water policy objectives into other policies, and addressing the knowledge gaps. The Blueprint review has been closely linked to the 2020 Strategy and the 2011 Efficiency Resource Roadmap and a number of issues and various challenges have emerged:

• Over half of Europe's river basins will fail to meet the 2015 target of meeting good ecological quality status;

• Ecosystems are 'weakening' due the pressures on European waters and more that 50% of these waters have been subject to hydromorphological modification;

• Diffuse pollution from agriculture and urban areas remain a major pressure in Europe's waters;

• The areas or Europe prone to drought and the countries affected have nearly doubled in the past decade;

• Water use is exceeding water availability in many areas of Europe. In terms of water abstraction measured against long term availability, the Water Exploitation Index (WEI) shows that Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Germany, Italy, Macedonia, Malta, Spain, and the United Kingdom (England and Wales) are already water stressed. Cyprus has a dangerous WEI of nearly 70%;

• Water efficiency is poor in terms of water use and water loss;

• Water pricing is currently inadequate and does not incentivise more efficient water use;

• Governance across the region is mixed and poor policy development leads to weak management of water resources;

• Data monitoring and data sharing is currently inadequate – knowledge of groundwater resources is poor – significant data is being generated for WFD but it is often not readily accessible;

• The density of Europe's population and the need to manage an increasing pattern of urbanisation, coupled with increasing consumption of 'water resources'.

Flooding and Drought

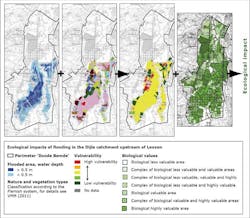

Linked to these issues is a fundamental need to increase our understanding of biodiversity, green infrastructure and our thinking about water in terms of green, blue, grey forms and consumptive and non-consumptive uses. The situation is further complicated by the changing climate and the expected increase in both flooding and drought incidents. A look at the past 10 years demonstrates that there has been an increase in the incidence of both these phenomena and they can often occur in the same area. Set to increase in frequency, this puts pressure on both water use and land use.

If we then add in the flow of water around Europe, as goods are bought and sold, the water component of these products (embedded water) becomes an important consideration, particularly where goods are produced in water scarce areas and are then sold to less water stressed regions. Spain is the first country in Europe to incorporate water footprint standards into its River Basin Planning and there is increasing interest in incorporating such thinking into water resource management.

Avoiding silo thinking from water and farming

Taking account of water footprint, thinking leads directly to a more complicated challenge: integrating WFD objectives into the reform of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). Here there is a need to introduce proper water pricing, integrate wetlands into agriculture systems and develop different approaches to using farmland for flood risk management, drainage – in other words, the reintroduction of natural retention systems. Such integration is key for water quality as well as resource management.

The European Innovation Partnership on Agricultural Sustainability and Productivity could be an important element in this integration. Bringing such thinking into CAP reform would also ensure that food and water were more integrated at the policy level and ecological considerations were more evident in agricultural practices.

In terms of urban pollution, the major issues are still emerging as the patterns of rainfall and flooding are becoming a lot more variable. Data suggests that from 2000 onwards, flooding in northern Europe is becoming more frequent. This creates stormwater system problems and other runoff issues from the urban environment – all countries need to develop Urban Pollution Manuals and integrate thinking on sustainable drainage systems (SUDS) into urban planning and development.

Integration & Delivering efficiency

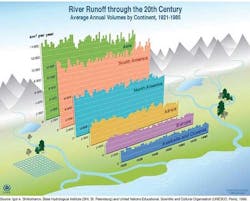

Underpinning policy integration is a need for proper water accounting system: one that looks at balances in terms of water flows, volumes and abstractions and use on a river basin and or national scale. Such a system would demonstrate where and how water is being used through the economy both internationally, externally and across river basins. The information should be linked directly into Drought Management Plans as this would help policy makers who may in the future have to decide between water for ecosystems and water for industry and/or human consumption.

Water accounting systems would also allow for integration of climate data and changing rainfall patterns into planning decisions. This must lead to better and a more effective way of prioritising water resource management solutions. Linked to this system is the need to improve water efficiency measures. This is not simply reducing water loss, though in some EU countries this would, in itself, produce significant resource improvements. It must include wide spread metering coupled with effective pricing policies for domestic, industrial and as mentioned, agricultural customers.

The Euroean Commission has taken steps towards developing an efficiency focus. The European Innovation Partnership on Water has been established to speed up the development of water innovation; stimulate the uptake of innovative products by the water sector and society at large and support sustainable growth and employment in the sector. There are five themes that will be explored: water re-use and recycling; water and wastewater (including resource recovery); water-energy nexus; flood and drought risk management and ecosystem services. These five themes are interlinked with three cross-cutting themes – water governance; decision support systems and monitoring; finance for innovation – with smart technology identified as an enabling factor. Will this change the dynamic of WFD implementation? It is a step forward in terms of developing more coherent approach towards water innovation and efficiency but there are still the fundamental policy challenges. The water-energy nexus looks at energy use in the sector and production but fails to consider the indirect issues of biofuels! Water Governance is not focused on policy integration of water objectives across the EU.

Where next? Taking things to their logical conclusion, there has to be complete policy integration across the EU, combined with a system for valuing water effectively. Water security must be placed at the heart of human security, national security, food security, energy security and climate security. The Water Framework Directive must therefore be integrated into the EU Trade Policy; the Habitats Directive; EU objective for Territorial Cohesion; the implementation of renewable energy targets; the EU White Paper on Adapting to Climate Change; EU Transport and Energy & Mining policies; and as mentioned already, future directions of the EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP.

The future

The future must achieve the right balance or tradeoffs between all these sectoral interests. This approach and this thinking must also be reflected in each member state. The Water Framework Directive, like many pieces of EU legislation, set timescales and frameworks that have a future time horizon, setting out where we want to be by a certain date. This is not only essential, it is extremely credible.

However, the legislation enacted in member states still has a strong element of reactive thinking. The Water Blueprint will help to change this but we should be encouraging water to be a key part of education systems within each member state. This should not be an objective but an action.

To manage the future, education about water must start as early as possible at school. This will not only help us to better manage this precious resource but it will also ensure that people know about water no matter what career path they take – integrated thinking would then happen naturally. Setting this as a goal would surely mean that the WFD was properly implemented in the future.

Author's note: Paul Horton is director of international development at CIWEM (the Chartered Institution of Water and Environmental Management). For more information on CIWEM, please visit: www.ciwem.co.uk