Creative Financing Tools to Fund Water Infrastructure

By Dave Dornbirer

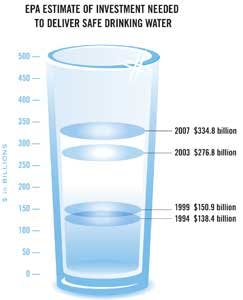

Water: it is one of our most vital resources but increasing demand and aging systems have stretched the U.S. water infrastructure to its limits. Both the EPA and the American Water Works Association estimate that the investment needed to update or replace existing water and wastewater systems over the next 20 years is in the hundreds of billions of dollars. At the same time, the economic crisis has reduced the financial resources of our nation's municipally owned water and wastewater utilities and eroded sources of public financing.

The municipal bond market, once a major source of funding for water infrastructure projects, remains a viable option for large cities but can be difficult for rural communities to access. A down economy continues to strain the budgets of state and local governments, which has resulted in a few high-profile municipal bankruptcies. As a result, many providers of bond insurance have exited the market. For those that remain, rates have increased so dramatically that it is has become unattainable for small communities, and investors have limited appetite to invest in bonds without this credit enhancement.

Federal budgets are equally strained. While the USDA will undoubtedly remain an important resource for utility service providers, no one agency can meet the increasing demands of the industry without significant funding increases. Tracy Mehan, principal at the Cadmus Group and former assistant administrator for water at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, noted that "the federal government is borrowing 40 cents on every dollar it spends. Until Congress gets control of the national debt, there is little chance of any new water infrastructure funding coming out of Washington. It is time to introduce innovative financing and private equity into the water sector."

Infusing private capital into rural America has been a significant priority for the past several presidential administrations. While there are existing programs, such as USDA loan guarantees, that do this quite effectively, it is likely that banks will need to play a more prominent role in the future — whether alone or as part of a public/private partnership.

USDA Loan Guarantees

For more than 30 years, the USDA Rural Utilities Service (RUS) has set aside funds to guarantee the repayment of loans from commercial lenders to water utilities. For the borrower, the application process is simple but lengthy. It can take anywhere from one to six months to process. Loans of up to $5 million are approved at the state level, but larger amounts require additional federal approvals. The duration of the application process can create a significant delay in the final completion of a project, but receipt of the guarantee offers substantial financial advantages.

Because an RUS guarantee covers up to 90 percent of the total loan value, the lender's risk is greatly reduced, making it more likely to offer attractive terms such as lower rates and longer repayment schedules. With an RUS guarantee in place, a lender with a standard 20-year repayment term may be willing to offer a 30-year term, lowering the borrower's monthly payments and increasing cash flow. While lenders often pass the USDA's required one percent fee on to the borrower, the improved terms usually compensate for any additional cost.

Though funding for USDA Rural Utility Service guarantees has remained level in 2012, the program's future is currently in question. The proposed presidential budget has no allocation for loan guarantees in 2013 and the contents of the final federal budget remain to be seen.

Interim Financing

Interim financing, another example of collaboration between the USDA and commercial lenders, has seen some success but has not been used consistently. When speed is of the essence, interim financing can help to accelerate the completion of a project. Organizations receiving loans directly from the USDA are often required to first obtain commercial financing to fund the construction phase of a project. Though it would seem to add an additional step, the process benefits both the USDA and the borrower.

Interim financing is provided in the form of a line of credit from a commercial lender. Borrowers can obtain multiple advances throughout the construction phase, which can reduce interest expense while providing reliable payments for contractors. At the end of construction, borrowers establish a USDA loan that is used to repay the line of credit. Although the USDA makes no explicit guarantee of repayment to providers of interim financing, most lenders rely on the USDA commitment to lend and consider the risk to be very low.

In addition to fulfilling the government's goal of furthering relationships between rural utilities and commercial lenders, interim financing eliminates the need for the USDA to provide construction advances. Processing these frequent advances can be cumbersome for the USDA and is more easily accomplished by a commercial lender, for whom they are common.

For the borrower, interim financing preserves the maximum loan term available from the USDA, reducing average monthly costs during the life of the loan. In some cases, the USDA offers a short period (typically 2 years) in which the borrower may make interest-only payments on the loan. This allows the utility to ensure that projects are well established before taking on the full financial burden of repayment. By delaying the start of the USDA loan, the borrower also delays the start of the clock on the interest-only period.

Project Finance

For utilities seeking funding outside the USDA system, a financing option known as "project finance" can offer an attractive alternative. The term refers to the long-term financing of a water infrastructure project owned by a single-purpose project company. The benefit of this financing option lies in its flexibility and the allocation of risks among the appropriate parties.

After forming a public-private partnership, municipalities and private equity sponsors form a stand-alone project company, effectively limiting the liability of all parties. The heart of this deal is the DBOF agreement, which stands for Design, Build, Operate and Finance. DBOF lays out each party's responsibilities — such as plant specifications, delivery schedules, revenues and permits. The project company's revenues come from the user fees determined by the municipality. If the DBOF is the heart of a project, rate-setting is its lifeblood. Ensuring that the project's revenue sources are transparent and easily modeled is vital in order to obtain the most attractive financing terms. In determining these terms, lenders rely solely on the contracts executed by the project company and the cash flows generated by it.

The flexibility that project finance provides allows water utilities to upgrade systems in a timely fashion while ceding most of the risks to third parties.

The Future of Finance

Clearly, the strength and integrity of our nation's water infrastructure is critical to its long-term health. Though the financial cost of upgrading or replacing that infrastructure is daunting, the cost of ignoring it may be catastrophic. A number of smaller communities are choosing to bypass the issue entirely by outsourcing their needs to larger rural water systems or contract operators but this is not always a viable option.

Water utility administrators must look carefully at the financial alternatives available to them and balance the pros and cons of each against the needs and priorities of their systems. Government funding is far from certain and the process of obtaining it can add significant length to a project's timeline, yet it often offers the best financial terms. Interest rates for private funding are often higher but borrowing through a commercial lender can significantly increase speed to market. The creative combination of public and private financing may offer the best of both worlds, helping to ensure the future of our nation's water infrastructure.

About the Author: David Dornbirer leads the Water Services lending team in the Rural Infrastructure Banking Group of CoBank, a cooperative bank serving vital industries across rural America. He is responsible for a portfolio in excess of $1 billion of loans to more than 80 not-for profit, investor-owned, and public-private partnership water, wastewater and solid waste companies across the United States. He has more than 13 years of experience advising and lending to companies in the water and energy sectors.

More WaterWorld Current Issue Articles

More WaterWorld Archives Issue Articles