Capital Optimization: Deploying Capital Wisely

by Fred Jennings

The EPA forecasts capital expenditures in the U.S. water utility industry to exceed $1 trillion over the next 20 years. The federal stimulus package alone will direct $19 billion for clean water, flood control and environmental restoration investments in the next 24 months. Whether the spending drivers are shovel-ready projects related to stimulus funds or typical capital projects necessary to manage day-to-day expansion and replacements in water and wastewater utilities, the U.S. will deploy enormous sums of “capital” monies.

The Color of Money

Some utilities act as if there is a difference between capital and O&M dollars, as if they are different colors. But the fact remains that both capital and O&M expenditures require the same green money and all spending strains the enterprise cash flow.

Despite the similarities, differences do exist in the way capital and O&M expenditures are scrutinized. Annual O&M budgeting often progresses through a structured development and review process with a great deal of scrutiny and justification. There is a transparent relationship between the expenditure and the results. In contrast, capital monies are often more complex, involving multi-year projects with myriad impacts and benefits that cross numerous functions. Yet, ironically, capital projects often receive a less thorough review.

Many organizations are reluctant to promote strong challenge to assumptions that might impact customer growth or service quality. Thus many projects get authorized with little hard justification. But this is precisely the area where we need to scrutinize capital spending to ensure we receive greatest value. In typical capital projects:

- Investments made today are usually for projects with long life spans, e.g., 20 to 50 years<

- The funds flow often involves debt obligations that will burden the utility for 20 to 30 years both directly and in the performance against those bonds (affecting debt rating and cost of capital)

- For growth-related projects, there can be a delay between the projects that serve that growth and the revenues to fund growth

A Better Approach

In an effort to manage capital spending, utilities have tried many approaches, including applying various prioritization schemes and asset management techniques. Frequently there is some rank ordering of projects with a line drawn across the list when the budget level is reached. Quickly cutting projects may gain a one-time reduction, but most often results in higher long-term cost implications. The problem with these approaches is that they address the project as it is presented as opposed to investigating aggressively the underlying justification. But the complexities of capital spending do not lend themselves to simple cost cutting. Competing needs and interrelated priorities require a more sophisticated approach.

To address this universal challenge, a more comprehensive process—Capital Optimization—is needed. Capital Optimization involves a high-profile and high-value enterprise-wide initiative targeted at fundamentally revisiting the decision criteria and mission-critical business processes used to identify and authorize capital projects. Instead of looking at individual projects and eliminating or reducing them, Optimization investigates the core processes in the project lifecycle and looks at how projects evolve from identification of need through to a closed project.

In that review, Optimization uncovers and examines perceived project “drivers” that propel a project to approval and completion. Even where a structured lifecycle process exists with lots of activity, it is uncommon to find objective and unbiased project value assessments. Similarly, most entities are ill-equipped to uncover unsubstantiated requirements that can masquerade as mandatory criteria, unrealistic or untested benefit claims and “pet” projects that do not reflect broad enterprise endorsement.

The Capital Optimization process is tailored to a specific organization's need, but in a typical engagement, the process involves six steps:

- Background and Data Collection

- Capital Program Review

- Program Management Approach

- Staffing and Organization

- Opportunities and Improvement

- Implementation Roadmap

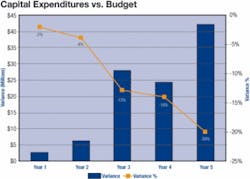

After Task 1, Background and initial Data Collection, the optimization process looks at the capital program in the aggregate. Step 2, Capital Program Review, examines the longer term trends such as annual budget versus actual spending, distribution of project sizes and spending trends by project drivers or categories. This analytical approach can identify programmatic issues affecting how a company manages capital resources:

While each organization may have its own business process design, organizational oversight, and responsibility assignments, the elements of delivering a project take place in a similar fashion. So with a sense of how and on what projects capital funds are spent, Step 3, Program Management Approach, looks at the capital program in detail by examining the steps in the project lifecycle:

- Work identification

- Project determination

- Project alternatives

- Justification

- Authorization

- Budget & Funding

- Initiation & Execution

- Project Management

- Closeout

In many instances, specific criteria for identifying project alternatives, justifying a project approach and authorizing that project under specific conditions are poorly defined or absent. Under the guise of necessity or when corporate performance metrics are misapplied (such as safety improvements at all costs), capital is spent that appears to be warranted but 1) is not necessarily linked to enterprise goals and performance metrics, 2) responds to wants, not needs, 3) does not adequately consider higher value alternatives, and 4) is not well peer-reviewed and internally vetted.

Instead, each step of the project lifecycle should be carefully analyzed, tested and realigned as necessary with the following in mind:

- Projects should be linked with company goals and strategies – this provides the highest level of investment guidance.

- Project/capital planning and annual budgeting processes should be separate but synchronized – recognize that they serve different needs.

- Each step in the project lifecycle must reflect clear tasks, responsibilities and authorities.

- Enterprise capital planning and budgeting (e.g., a new CIS) should be transparent and reflect an endorsement process by the company leadership team.

- All projects should reflect consistent and mandatory analytical rigor.

- Project prioritization criteria should be defined at the enterprise, service (utility) and division levels.

- There should be a clear and empowered governance structure – a capital review or steering committee should oversee capital spending on behalf of the enterprise, and from that enterprise perspective, adjudicate resource apportioning across competing services and departments.

- Prudent and structured business risk should be incorporated into investment decision-making.

- The cultural strengths and impediments must be recognized. (Step 4, Staffing and Organization, specifically focuses on this topic.)

Conclusion

A Capital Optimization approach focuses on how to lower costs and/or deliver higher value without simply cutting project size. It first examines how the overall capital spending program serves the enterprise in its mission and goals. This macro-view can rapidly gauge whether the overall capital spending seems to be in alignment or has become derailed from consistently delivering enterprise value. Armed with this view, the micro-examination of each step in the project lifecycle can diagnose where improvements should be targeted. The combination provides a roadmap to refocus company processes, organization, roles, responsibilities and information tools to achieve sustainable long-term cost reductions.

For companies hoping to reduce capital expenditures, Capital Optimization offers a thoughtful and informative approach. Without optimization principals in place, simple cuts may negatively impact high-value projects while leaving low-value projects intact. Companies of all sizes are using an optimization approach to redirect investment decision-making toward enterprise value and away from traditional institutional beliefs and unsubstantiated assumptions. Redirecting capital expenditures toward value offers water utilities the flexibility to meet costly future challenges in water quality and water supply.

About the Author:

Fred Jennings is Principal and Senior Consultant at R.W. Beck. He has more than 25 years of experience in utility industry program design and implementation, strategic and business planning, and cost and performance management. He can be contacted at [email protected].