What will happen with the PFAS MCLs in 2024

The water industry is waiting for the U.S. EPA to finalize its pending regulations for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in drinking water — and the industry speculating about the effects of this final rule.

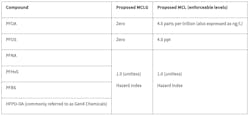

The regulation would set Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) for 6 major PFAS compounds in drinking water. But when will this regulation take place and how will it affect utilities?

A history of the PFAS MCLs

On October 18, 2021, EPA announced its PFAS Strategic Roadmap, which would lay out the agency’s approach to address PFAS from 2021 through 2024.

The roadmap predicated the timeline for a national primary drinking water regulation for two key PFAS compounds: perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS). According to the timeline, a proposed rule would come in Fall 2022 while the final rule would be implemented in Fall 2023.

This timeline was a few months short of the actual result: the proposed regulations for PFOA and PFOS — in addition to four other compounds — was announced on March 14, 2023, not Fall 2022. And, with 2024 already here, the final rule date did land in Fall 2023 either.

When the final rule will come

On December 14, 2023, EPA released its latest annual PFAS Progress Report, highlighting its accomplishments under the PFAS Strategic Roadmap. In this report, EPA says it now expects a final rule some time in early 2024. EPA Office of Water Assistant Administrator Radhika Fox affirmed this estimate in an interview with WaterWorld a few days later.

“I think they will stick to their timeframe,” said Claudio Ternieden, executive director fo the Water and Wastewater Equipment Manufacturers Association (WWEMA). “They have an action plan that reflects what they want to do and they’ve been keeping up mostly with that action plan.”

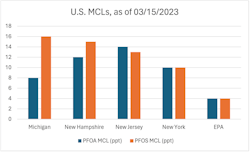

The final rule might be different from the proposed rule from March 2023, however. The proposed MCLs depart significantly from the precedent established by state PFAS regulations.

“It’s possible. I’ve been told from various sources that 4 and 4 [parts per trillion], as the actual finalized levels — those are being discussed as whether or not they’re too low,” said Mike McGill, president of WaterPIO. “When I’m asked what I think the right number should be, I look to the states. The states have really tackled this issue for years. They have polluters in their backyards. They set standards, like Michigan at 8 and 16 [ppt] for PFOA and PFOS.”

How the MCLs will affect water utilities

The final rule for this PFAS regulation will be a significant disruption for the drinking water sector.

First, the regulations will require treatment upgrades from many utilities, even for water systems that already treat PFAS in their drinking water.

Utilities in states with established PFAS regulations are already monitoring and managing PFAS, but this will not guarantee compliance with the EPA MCLs. The proposed 4 parts-per-trillion MCL for PFOA and PFOS is very low. Of the states that already have drinking water standards for PFAS, EPA’s MCL is lower than nearly all of them.

Utilities that have already implemented advanced treatment to deal with states’ PFAS MCLs may have to implement further treatment to meet these new regulatory demands.

“I have one client that, they’re under 4 right now,” said McGill. “But with drought, as we know, PFAS numbers can spike. They’re on a river, they don’t have a proven polluter. But with drought, if they go over 4 [ppt], it will cost them $4.5 billion alone to bring their plant up to speed on advanced treatment for PFAS. So there are these major cost considerations that, honestly, EPA has lowballed, and that utilities all across the country would have to pay for.”

Once the rule is finalized, utilities will have about three years to meet those standards. Many utilities will also be able to receive a waiver to extend that compliance deadline to about five years.

Second, utilities will encounter a new communications challenge with these PFAS regulations. Many water systems will need to enhance their communication to maintain public trust.

“Many states have already set their standards, they’ve already been out front on this issue,” said McGill. “But for the vast majority of utilities, they’ve never spoken the word PFAS. They’ve never tried to explain it to the public. And they need to get out front and do so now.”

If the public does not hear about PFAS management from the utilities themselves, there stands a risk that they may depend on dubious sources, like social media, to learn about these pollutants.

How well-prepared are utilities?

Data on utilities’ PFAS regulation preparedness is sparse. It is clear, however, that some utilities are prepared while others are not. In a reflection of that: some people are confident in the water sector’s position to respond to the final rule, while others are less optimistic.

“I would say the sector is poised, especially at a time where there is more funding available than has been before,” said Ternieden. “Congress has made a lot of money available; EPA has worked hard to get that funding out the door.”

“You still have people in water that say ‘this is no big deal. It’s hype. We’ll deal with it when it comes just like we’ve dealt with everything else,’” said McGill. “The problem with that is this is unique. If you can’t meet these standards, you are going to need advanced treatment. . . And the UCMR5 data so far shows that we could be looking at upwards of 3,00 or 4,000 utilities in this country that will need advanced treatment for FPAS — and basically all at the same time.

“There’s not enough out there,” said McGill. “There’s not enough treatment systems, there’s not enough media, there’s not enough money, you name it. We’re going to have thousands of systems needing advanced treatment all at one without having the money to pay for it and potentially without that media or those treatment systems even being available.”

The capacity of labs to test water samples will be challenged, too. A nationwide surge in PFAS testing demand will be a shock to labs’ capacity. In addition, an expected rise in lead testing in 2024 and 2025 will exacerbate this supply chain issue.

However, the water sector has always recovered quite well from disruptions. Ternieden feels optimism for the water sector’s position to respond to PFAS.

“Utilities and their suppliers are very good on planning. They’ve done a good job with that,” said Ternieden. “They are good about making sure they’re ahead of the curve.”

However, he also recognizes the significant and unique challenge of regulating PFAS.

“PFAS is one of those things that I think may have caught the sector a little off-guard more than other [pollutants] — and faster — for a number of different reasons,” said Ternieden. “Probably because there’s so many categories, so many different ways of looking at it and the levels of risk in these small amounts. You want to go on and on how this is different from other things — like mercury, dioxin, microplastics or others. There are some people that still believe this is just the latest fad, but we don’t think so because it’s so pervasive — more than anything we’ve seen.”

About the Author

Jeremy Wolfe

Jeremy Wolfe is a former Editor for WaterWorld magazine.