“…As soon as it comes into contact with the waves of the sea and is submerged [it] becomes a single stone mass, impregnable to the waves,” first century author Pliny the Elder wrote of Roman concrete. But how? Scientists have struggled for centuries to determine the secret ingredient that fortifies the still-standing coastal structures built by ancient Romans 2,000 years ago.

Whereas modern concrete decays when exposed to saltwater, the concrete used by Roman builders was designed to grow stronger over time. The formula, a mixture of volcanic ash, quicklime, and chunks of volcanic rock, relies on a straightforward process called the Pozzolanic reaction. But as researchers recently discovered, the material undergoes a very complex chemical reaction when it comes in contact with seawater.

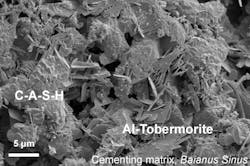

Scientists closely observed the microscopic structures of Roman concrete samples using a spectroscope and high-tech imaging equipment including microdiffraction and microfluorescence analyses at the Advanced Light Source beamline 12.3.2 at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. In doing so, they discovered that a rare reaction took place that produced aluminous tobermorite crystals.

These crystals formed in the cementing matrix when seawater percolated through cracks in the Roman concrete and reacted with the mineral phillipsite, found in volcanic rock. As seawater leached minerals from the concrete and re-solidified as crystals in the pumice particles and pores, it reinforced the structure. Roman concrete is an outstanding example of a building material that interacts with its environment.

These findings are fascinating. Furthermore, as investment in infrastructure repair becomes an increasingly high priority and as communities worldwide prepare for rising sea levels, discoveries such as this may have a profound global impact. Innovations in 3D printing, nanotechnology, and the development of new construction materials are already emerging as essential components of a sustainable future. And it seems that studying the materials of the past may help us create structures to withstand the environmental challenges of the next centuries. What are your thoughts?