BILLED WATER CONSUMPTION is the lifeblood of utilities in the US. With billed water consumption comes revenue that utilities employ for operations and maintenance—it allows for the long-term investment in the economic security of our communities through capital improvements and resource sustainability, and it allows for investment in the activities and infrastructure needed to protect public health. Without stable revenue, our cities and communities are at significant risk.

With declining federal and state funds for infrastructure, our water utilities are more on their own when it comes to providing safe, reliable, and cost-efficient water to citizens than at any other time in the past.

With rate structures that are skewed to volumetric sales, however, the overall financial sustainability of a utility—and by extension the health of our communities—is often predicated on selling more water. In an era of increasing water volatility, expecting continuous growth in water sales is a perilous premise.

The reality is we are using less water. Driven by structural, voluntary, and regulatory conservation measures, our utilities are delivering less water and thus recovering less revenue. Fixture efficiencies in toilets, taps, and other uses; public awareness; and regulatory-mandated conservation measures, such as California’s drive to reduce deliveries by 25%, have each taken a bite out of utility revenue.

This impact is all too real for the managers of our utilities. Public water withdrawals declined by 5% from 2005 to 2010, the first reduction in 50 years. More than 35% of utilities are experiencing year-over-year reductions in revenue, and 80% of utilities are experiencing declining or flat volumetric sales. Worryingly, this trend is occurring alongside an ever-widening investment gap for water infrastructure. The 2016 American Water Works Association (AWWA) State of the Water Industry report calculates that $21 billion will need to be invested annually in American water infrastructure to meet current and anticipated demand. That same year, federal funding for water infrastructure reached less than 5% of that projected requirement.

For our water utilities, the fact that Americans are consuming less water is becoming an existential threat.

To meet the needs of today and the future, water utilities are seeking ways to improve and grow revenue. The routine response to declining revenue is to raise rates. When water is inexpensive, revenue recovery through rate increases is often an effective policy. In many communities, however, the cost of water is reaching a point where rate increases drive further conservation. In this elastic consumption-price zone, utilities are finding that they are not recovering the expected revenue from rate increases. In addition, the optics of “punishing” customers for conservation by increasing rates is often a public relations nightmare for our utilities.

The solution to this conundrum, then, must be to maximize the revenue efficiency of our utilities. To achieve financial sustainability, utilities must ensure that they collect all the available revenue provided through existing rates, while monetizing every drop of water. This means getting better at managing the measurement of our water, better at eliminating non-revenue water, better at billing and collections, and being faster at detecting and correcting errors that destroy revenue.

These programs of revenue assurance can be significant contributors to the financial security of out utilities.

MANAGING METER ACCURACY

Meter accuracy is a fundamental element of revenue assurance. While AWWA standards require that meters meet specified accuracy requirements as they leave the factory, there is no standard for operational maintenance of that accuracy.

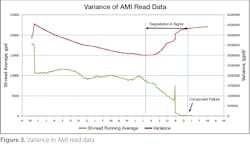

A meter’s physical accuracy depends on a multitude of factors including its age, volumetric throughput, installation configuration, the flow rate range, and water quality. Once installed, the meters themselves are typically untouched for 15 to 20 years. Utilities operate on blind faith that these meters will continue to operate accurately and reliably without intervention for decades. In reality, studies on meter accuracy as a function of time and volume indicate that accuracy degradation can occur immediately and without warning. Having time-based or sample-based replacement and inspection programs, for example replacing meters every 10 years, leaves the utility in a position of possibly losing revenue for an extended period of time.

Utilities can benefit significantly by upgrading their metering systems and deploying data-based monitoring programs to identify potential failing meters quickly to reduce the potential for revenue loss.

A recent meter exchange in a southwestern water utility serves as a prime example of how AMI and the analysis of granular data can preserve and protect utility revenue flow. The 20,000-meter water utility, like other utilities across the US, was experiencing increasing non-revenue water. The utility undertook a meter upgrade program which improved meter accuracy, decreased non-revenue water, and increased revenue.

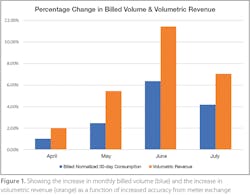

In Figure 1, an analysis of meters with the same customers’ pre- and post-meter exchange showed increases in billed volume up to 6.4% during the peak usage months generating a volumetric revenue increase of 11.4% (based on the 2016 rates).

Advanced Metering Infrastructure (AMI) is the integrated system of smart meters, communication networks, and data management systems that helps automate the meter reading process. Possibly more important, however, is that AMI provides improved usage granularity to better understand consumption in real time, increased speed of response to abnormal metering conditions (reads, tamper, leaks, etc.), and the data necessary to provide real-time meter health condition analysis. With information from an AMI installation, the data environment is becoming rich enough to allow meter diagnostics to be performed without actually visiting the meter.

And that allows us to ensure that revenue does not leak away.

Protecting revenue is as much about the data as it is about the equipment. Having data systems that can identify anomalous activity or errors in services, rates, and other attributes is a key component of getting all the revenue billed and collected.

Without sufficient safeguards in place to protect the data, as connections and billing systems grow in the evolution of a utility, it is not uncommon for the electronic records used for billing and the physical installations on the ground to become decoupled. The result is leaking data that results in revenue loss.

Some of the sources of these data leaks include:

- Water theft from bypassed meters

- Unauthorized connections

- Meter missing from the billing inventory

- Meter installation errors

- Improperly sized or specified meters

- Data transcription errors, such as meters not correctly mapped to customer information

- Incorrect billing codes in the billing platform (meter size, class, etc.)

- Incorrect ancillary attribution (sewer, garbage, pressure zone, etc.)

Unfortunately, many legacy water billing platforms are not equipped with the ability to identify these data errors, nor are they capable of consuming highly granular data generated from AMI systems. But adopting newer platforms that are capable of handling this type of data and ensuring data integrity can also represent a significant operational risk for utilities.

Advances in cloud-based service models to transition a utility to a modern meter-to-customer platform go a long way to solving these problems. At FATHOM, we have developed delivery strategies that allow utilities to minimize their risk, maximize their service delivery, and enjoy the benefits of continuous improvement, while providing cost certainty today and in the future. FATHOM combines meters, implementation, software, services, and financing into a single contracting vehicle that aligns operations, equipment warranty, and finance to provide significant risk mitigation for cities.

With a new data-driven approach to the meter-to-cash vertical, utilities are put in active control of their revenue, collecting all the revenue that their existing rates provide and ensuring all meters and services are billed accurately and efficiently.

Investment in meter data management and customer information systems that help find revenue in data end up being self-funding, helping utilities confront declining revenues and the widening infrastructure investment gap. In the case outlined above, the utility saw a dramatic increase in revenue within a year, justifying the investment in improved metering infrastructure. Utilities should not fear investment in new technology, but should rather embrace the efficiencies they will bring to their operations. In fact, utilities can use this newly-found cash flow to help free up further cash by reducing costs from other operations in the utility, which in turn can be reinvested in other technologies that help streamline operations and reduce costs.

In the end, the good news for our utilities is that it is possible to sell less water and make more money.REFERENCES

American Water Works Association, “2015 State of the Water Industry Report: Steady-State or State of Change?” www.awwa.org/publications/journal-awwa/abstract/articleid/53605400.aspx

American Water Works Association, “2016 State of the Water Industry Report: The Cornerstone Needs Support,” www.awwa.org/publications/journal-awwa/abstract/articleid/59986755.aspx

Jeff Hughes, “Financial Revenue Trends and Sustainability,” University of North Carolina Environmental Finance Center, 2014, www.efc.sog.unc.edu/resource/financial-revenue-trends-and-sustainability