EPA Report Details Progress Of Drinking Water SRF Program

The Environmental Protection Agency has issued a Report to Congress that describes the progress that states have made in the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund program (DWSRF) since the first funding was awarded in March 1997. The report uses information provided to EPA by states through June 30, 2001.

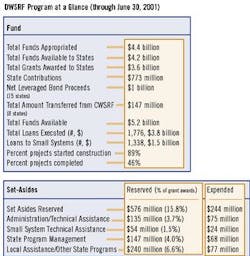

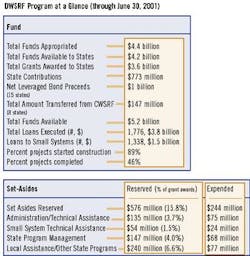

Using funds made available through federal grants, state match, net bond proceeds, transfers from the Clean Water State Revolving Fund program (CWSRF), earnings and repayments, states have provided public water systems with close to 1,800 loans totaling $3.8 billion, according to the report. This represented 72 percent of the available funds — $1.4 billion remains available for loans.

Weighted average interest rates for loans in the program have generally ranged between 2 and 4 percent. That compares to the 20 year Bond Buyer Index interest rate (a proxy for market rate), which ranged between 5.1 and 5.8 percent for the same period.

Congress has acknowledged that the program's low interest rates may not make these loans affordable for some systems. Therefore, the SDWA allows states to provide additional subsidies (e.g., principal forgiveness, negative interest rate loans) to systems identified as serving disadvantaged communities. States may also extend loan terms to up to 30 years for these systems.

States determine which systems are disadvantaged in accordance with state-developed affordability criteria. Twenty-nine states have provided assistance to systems through a disadvantaged assistance program. Sixteen states offered principal forgiveness, 18 offered extended loan terms, and 10 offered both types of assistance.

The SDWA also placed a special emphasis on providing assistance to small systems serving 10,000 people or fewer, requiring that states provide a minimum of 15 percent of their available funding to small systems. States have far exceeded that requirement, with 41 percent of loan funds going to small systems. The actual percentage of loan agreements provided to small systems (75 percent) is considerably larger, which reflects the fact that the average dollar amount of loans to small systems is less than that for larger systems.

When looking at how funds have been directed in the DWSRF program, treatment represented the largest percentage of project costs (43%), followed by projects to address transmission and distribution needs (32%).

The law requires that states give priority to projects that are needed to protect public health and ensure compliance with the SDWA. While solutions to public health and compliance problems may require a system to address any of the four categories of infrastructure (transmission and distribution, treatment, source and storage), many projects require costly treatment solutions.

Set-Asides

The 1996 Amendments also included several other new programs and requirements aimed at strengthening the technical, financial, and managerial capacity of public water systems and preventing contamination of sources of drinking water. The law allowed states to use up to 31 percent of their grants to support these types of activities. States must describe how funds are used in workplans, most of which range from one to three years.

Nationally, states have reserved approximately 16 percent of federal grants for these purposes, although on an individual state basis the amount reserved has ranged from 7 to 31 percent. Through State Fiscal Year (SFY) 2001, states had expended 43 percent of the $576 million in funds they reserved to conduct set-aside activities.

EPA had concerns about slow progress in expenditures of set-asides, but expenditures have increased from 9 to 42 percent from SFY 1998 through 2001.

States have funded a wide range of activities through the set-asides that fall under several broad categories, such as:

• Enhancing the technical, financial, and managerial capacity of public water systems in an effort to make systems more sustainable and to promote long-term compliance with the law.

• Enhancing operator certification programs to ensure that operators of public water systems are properly trained in the operation of facilities and meeting requirements under the law.

• Providing technical assistance to small systems, which often have limited financial resources and face a great challenge in meeting new SDWA requirements.

• Facilitating partnerships with institutions of higher learning, water system professional and trade organizations, government officials, and the general public to carry the message of the importance of drinking water safety.

• Enhancing support for state drinking water programs to implement new programs and build existing programs in the areas of regulatory oversight, data systems, and source water protection.

• Promoting source water protection to manage potential sources of contamination and prevent pollution from reaching sources of drinking water.

Programmatic Effectiveness

The report includes a discussion of several factors considered in an effort to gauge the progress and effectiveness of the program. States have received 87 percent of the federal grants available to them and initiated construction on projects for 89 percent of the executed loan agreements. When considering the return on federal investment in the program, the numbers are impressive. States have used several sources to add funds to the program, exceeding the amount of federal dollars provided. After removing federal disbursements for set-asides, the national disbursements as a percent of net federal outlays for infrastructure projects is 160 percent. In other words, for every $1 in funds drawn from the federal government, states have disbursed $1.60 for project construction.

More than one-third of the agreements funded have gone to systems that are out of compliance with health-based drinking water standards, to develop projects that will return or bring them into compliance. With respect to addressing economic need, 26 percent of all loans have been provided to systems identified as disadvantaged. The program has also given many small systems access to infrastructure financing and technical assistance through the set-asides.

Program Issues

As with any new program, states have faced challenges in implementing the DWSRF program. States have had to make decisions on how to direct funds and structure programs in a manner that addresses their highest priority needs and ensures that funds will be available to provide assistance in the future.

At times, these goals can compete with one another, particularly in determining how much of the funding to direct to set-asides, and in making decisions on the types and amount of assistance provided to disadvantaged systems.

EPA has tried to work in partnership with states to identify solutions to several issues impacting implementation of the program. Addressing future challenges will likewise require partnerships between public water systems; local, state and federal governments; and the general public. These challenges include addressing drinking water infrastructure needs, ensuring the sustainability of public water systems, and ensuring the security of facilities. While the DWSRF primarily addresses the first of these challenges, it can also be structured and implemented in a manner that addresses the others as well.

For example, states are using DWSRF set-aside funds to implement capacity development strategies focused on improving the technical, financial, and managerial capacity of water systems. States can encourage use of tools that enhance sustainability such as rate structuring, asset management, consolidation, public-private partnerships, privatization (where appropriate), and use of affordable technology through their DWSRF set-asides or by including conditions within infrastructure loans.

With respect to security, states can help systems assess their vulnerability to security threats and then take measures to address those threats.

The report discusses several issues that arose during the early years of program implementation as well as issues raised by states and other stakeholders that could benefit from changes to current law. For example, EPA agrees with stakeholders that have requested an extension of the flexibility to transfer funds between the two SRF programs.

This article was based on information drawn from the Executive Summary of the "Drinking Water State Revolving Fund Program: Financing America's Drinking Water from the Source to the Tap - A Report to Congress." A copy of the report may be found in PDF format at www.epa.gov/safewater/dwsrf.html.