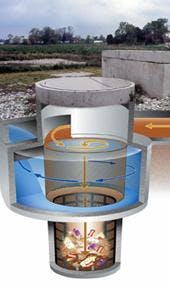

The CDS system relies on water hydraulics, gravity and a non-blocking screen. CSO water enters a diversion chamber where a weir guides the flow into the unit's separation chamber. A vortex is formed that spins floatables and suspended solids around the screen cylinder.

Click here to enlarge imageThe project is putting Akron on the road to compliance with the state's CSO regulations. It also won an American Council of Engineering Companies award for Commonwealth Engineers, Inc., of Indianapolis. As a bonus, the citizens of Akron get a clean lake that will be suitable for recreation and a beautiful new wetlands area (complete with 1,200 new trees) on what used to be 20 acres of unused lowland.

The best news is that the entire project cost just $700,000. Estimates to separate the sanitary and storm sewers came in at $4 million. Enlarging the treatment plant would have cost $1.1 million.

"If you look at the cost of this project versus the cost of separating our sewer system, I'd say we made a good investment," said Gerhardt.

CSO abatement has become a hot topic in Indiana, where many cities have limited budgets for major public works projects.

"Here in Indiana there are 106 CSO communities and they range in size from towns like Akron up to the big cities like Indianapolis, Fort Wayne and others," said Mark Sullivan, PE, of Commonwealth Engineers, Inc., of Indianapolis. "Most of the CSO regulations are unfunded, unless you qualify for a Department of Commerce grant, as was the case for the town of Akron. It's safe to say that most communities are having a tough time coming up with the money necessary to complete CSO requirements.

"I think the Akron project is a nice model to follow for other small communities that have a CSO problem," Sullivan said.

Akron's combined storm and sanitary sewer system was typical of many towns across America. Built in 1970, it consisted of 8-12 inch diameter pipes. The town has a small two-cell lagoon treatment system with a dry weather flow that averages 150,000-175,000 gpd with a maximum capacity of about 300,000 gpd.

According to public works superintendent Gearhart, any rainfall event of one-half inch or more was a potential problem for the system. During wet weather the overflow would be discharged into Town Lake. Overflows would occur about 20-25 times annually.

"Biologically the lake was in pitiful condition," said Sullivan, whose company was brought in as a consultant on the project. "It ranked as one of the most polluted lakes in the State of Indiana."

When engineers and consultants began reviewing Akron's situation, they quickly ruled out separating the sewers or enlarging the treatment plant. Those options were far too expensive for a small town budget. On closer examination of the problem they discovered that Akron had some natural characteristics that might provide a cost-effective solution.

"Akron was lucky. Everything flowed down to a low spot that was already owned by the city. It all worked by gravity," said Mark Harrison, now president of Natural Concepts Engineering, Inc. At the time he was a consultant with Commonwealth Engineers. "The CSOs flowed into a county drain tile which ran through the low land and then into the lake. We basically built the wetland over the county tile and intercepted the flow."

Both the influent and effluent ends of the wetland have a rock filtration system to help remove debris and reduce pollutants.

"Wetlands are excellent for removing dissolved BODs and dissolved nutrients," said Harrison.

They're also good at removing volatile solids, but can begin to fail if they become overloaded with solids.