By Sarah Fister Gale

Every drop of water on the planet has been recycled at one time or another, but when you talk about bringing wastewater back to potable standards, people get a little squeamish.

That public perception factor is one of the biggest hurdles for communities considering direct potable reuse (DPR) as a means of generating a reliable source of clean water when other resources aren't sufficient, said Wade Miller, executive director of the WateReuse Research Foundation (WRRF), a non-profit water reuse research organization that is leading efforts in applied research around direct potable reuse.

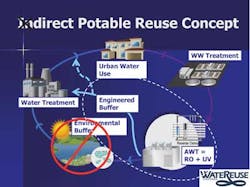

DPR is the process of treating wastewater to drinkable standards and returning it to the raw water supply without the use of an environmental buffer. Rather than mixing the treated water into an aquifer or reservoir (as you would with an indirect potable reuse [IPR] system), with DPR, the treated water is distributed immediately upstream of a drinking water treatment plant or directly into the potable water distribution system.

The technology exists today to return wastewater to drinking quality standards, Miller said.

The process involves putting wastewater through a three-step process. It begins with microfiltration to filter out larger particles, followed by reverse osmosis to remove contaminants and inorganic impurities, and the final step involves treating the water with ultraviolet light and hydrogen peroxide to kill any remaining bacteria and organic chemicals.

"By the time the water is through those three processes, it is near distilled quality," Miller said.

Despite proof that the treated water meets standards for consumption, U.S. communities have been slow to adopt DPR as a viable solution. Currently, the only example of a DPR system in operation is in Windhoek, Namibia, where highly-treated recycled water is put into a drinking water system that serves 250,000 people.

The direct potable reuse system in Windhoek has been successfully operating since 1968, but it was only recently that U.S. agencies and municipalities began looking at DPR as a viable option.

California leads the way

In 2010, then-Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger signed a bill that in part required the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) to investigate the feasibility of developing uniform water recycling criteria for DPR and to provide a final report on that investigation to the legislature by December 31, 2016.

In 2012, the WRRF and WateReuse California launched a fundraising initiative to support research for the DPR report and very quickly raised $4 million from 30 different water and wastewater agencies. "It's clearly an issue whose time has come," Miller said. "Research is the key to developing a sound scientific underpinning from whence we can impact public policy and gain public acceptance and regulatory support."

A few leading communities have already begun planning and building DPR facilities, including the Colorado River Municipal Water District (CRMWD) in Big Spring, Texas, which won approval for a direct raw water blending operation in 2011, and brought the plant online in April 2013. Direct raw water blending is a form of DPR in which treated water is blended with surface water in a raw water pipeline for distribution.

"CRMWD doesn't have a lot of alternatives," said Ellen McDonald, leader of the water resources group for Alan Plummer Associates, an environmental engineering firm in Fort Worth, Texas. "Their groundwater is poor quality, and they don't have a reliable supply of surface water."

These are the kinds of scenarios that spur communities to consider DPR, because they have few other options, said Guy Carpenter, PE, vice president of the Water Resources & Reuse Group at Carollo Engineers in Phoenix. "The main driver for the use of wastewater treatment plant effluent as a drinking water supply is water scarcity," Carpenter said. "For some communities in the United States, reclaimed water is the only supply of water they have or can access to meet demands, including for drinking water."

If utilities like CRMWD prove that DPR systems can work, more municipalities may begin considering them as viable options to address water scarcity issues, McDonald said. Indeed, CRMWD's success in winning approval for DPR spurred water districts in Brownwood, Texas, and Wichita Falls to pursue similar initiatives.

All of these DPR projects are looking to California's Orange County Water District Groundwater Replenishment System (GWRS) as a road map for their own facilities. The GWRS is an IPR system - it takes highly-treated wastewater that would have otherwise been discharged into the Pacific Ocean, purifies it to exceed state and federal drinking water standards, then puts it into the Water District's percolation basins in Anaheim, where it is naturally filtered through sand and gravel before returning to the drinking water system.

Even though the system uses an environmental buffer, the water is near distilled quality when the treatment process is complete and could potentially be consumed directly. The facility can produce up to 70 million gallons of high-quality water every day and provides 20 percent of the total water supply to the district's 19 municipal water agencies and 2.4 million residents.

A Regulatory Framework for DPR

Even though the technology has been proven, work still needs to be done around regulation and monitoring of DPR systems to ensure they are safe. There is currently no national regulation for water reuse or for the application of reclaimed water as a drinking water supply; there is, however, a lot of guidance and ongoing research to support its implementation, and every state is devising its own regulatory framework for the practice, Carpenter said. That's a critical step in gaining national acceptance for DPR solutions. "Communities need regulatory frameworks supported by good science to be able to consistently and reliably produce drinking water," he said. "Obviously, all water sources have varying levels of chemical and/or microbial contaminants in them, and the Safe Drinking Water Act requires conformance to primary and secondary standards before they can be used as drinking water."

When considering reclaimed water as a source, engineers must be additionally cautious about monitoring because of the higher concentrations of pathogens and trace organic chemicals in water from sewage, said Don Vandertulip, PE, BCEE, principal, and leader of the Tech Water Resource Group for CDM Smith, an engineering firm in San Antonio, Texas.

"Most people advocate a multi-barrier approach so that if there is a problem with one step in the process, you can still produce safe water," he said. But that has to be coupled with monitoring of water standards, with technology that can alert operators in real-time if the quality of the processed water falls outside of acceptable standards.

"Analytical instruments for inline monitoring continue to improve, allowing operators to quickly stop or divert water if something goes wrong," Vandertulip said.

However, even if regulations are enacted, technology and monitoring tools are proven to work, and early efforts by CRMWD and other utilities are successful, DPR should be evaluated carefully against other alternatives, McDonald advised. "If you have a good aquifer or surface water resource, indirect potable reuse may still prove to be less expensive and a more palatable option to the public."

If You Build It, Will They Drink?

Indirect potable reuse projects are also easier to sell to a community that's uncomfortable with the idea of drinking treated wastewater. But this is an issue that can be overcome.

"A challenge for the water industry is getting the public to focus on finished water quality achievable by the employment of treatment technologies and operations and management practices, rather than on the source of supply," Carpenter said. "As a nation, we are at the point where all sources of water need to be considered for any type of demand, whether it be domestic, agriculture, industrial, or environmental.

Once water-scarce communities understand the water quality that can be achieved through treatment steps - and the few alternatives they have to find clean, consistent drinking water, it is possible to win them over, Miller said. "The point is that you must engage the public, explain where the water comes from, how you treat it, and what quality you can achieve," he said. "If you are honest and transparent, they are generally accepting."

Though ultimately, demand alone will drive acceptance of DPR, on a case-by-case basis, Carpenter said. "The public water supply industry - and we as a water engineering firm - are not interested in pushing potable reuse. But we are interested in creating a framework so that those communities that have no other water supply alternatives can do it safely and reliably."

About the Author: Sarah Fister Gale is a freelance journalist based in Chicago. Over the last 15 years, she has researched and written dozens of articles on water management trends, wastewater treatment systems, and the impact of water scarcity on businesses and municipalities around the world.