Privatised water services can actually reduce competition in markets in which giant water companies win long-term contracts and supply equipment from within their vertically integrated corporate holdings, contend Jarmo J. Hukka and Tapio S. Katko of Tampere University of Technology.

International discussions on private sector participation in water services are largely biased given the current jargon that assumes the private sector has taken over the role of operators and/or owners of water and wastewater undertakings. Yet the vast majority of these undertakings is publicly owned and operated.

These public undertakings buy goods, equipment and services from private companies and hire private companies to implement capital investment projects based on competitive bidding. Current debates largely neglect these “mainstream” roles of the public and private sectors.

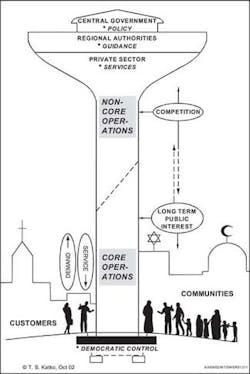

Figure 1.Outsourcing of non-core operationsto private contractorsthrough competitivebidding

Currently, the seven largest private multinational companies provide sewerage services to only approximately four percent of the world’s population, and water supply services to six percent of the world’s population. France, England and Wales represent a large portion of this privatised market; their combined coverage accounts for 3% of sewerage services and 2.3% of water supply services provided by the private sector to the world’s population. These oligopolists dominate the global water services market. When listening to most sessions at international conferences, one could assume that the public-private partnership (PPPs) approach is the “mainstream” and innovative private sector involvement always leads to increased competition and efficiency.

This was the case at the conference on “Water Policy: Allocation and Management in Practice” held at Cranfield University, UK in September 1996 where the authors presented their first paper on the consequences of privatisation, and continued to be the case at the Stockholm Water Symposium, held in August 2004. Similar ideas were presented in the August 2004 issue of WWI (Vol. 19, Issue 6) by van Dijk and Schouten: however other critical views have also been presented, such as those by Wolfe in WWI Viewpoint columns published in February 2002 and December 2003.

The private sector played the dominant role in the early and mid-1800s when modern water and wastewater systems were first established. In all western countries, except for France, municipalities soon assumed the responsibility and ownership of these services for several reasons. Unfortunately, many water experts and policymakers have overlooked this historical fact.

As noted, e.g., by Schramm (2004). “the new debate on privatisation of the water infrastructure is led without historical consciousness”. Based on US experiences, Melosi (2004), another historian noted that cities are particularly wary of multinational companies that have no local ties, but are the driving force of privatisation. Handing over control of water supplies and water delivery to the private sector is not the same as making a public good into a private one, but a “fundamental erosion of local authority well beyond more traditional tensions between city and region, city and state, and the city and the federal government”. Ever since the start of modern water and sewerage services, public undertakings have bought goods and services from private sector suppliers, manufacturers and consultants, and used private sector contractors.

International financial institutions have widely promoted the involvement of private operators or concessionaires since the mid-1990s. Yet the ambitious goals of these financiers were not reached as assumed and proved counterproductive a few years later. A representative of a leading financial institution admitted in 2003, “We and others largely overestimated what the private sector could and would do in difficult markets.” A recent World Bank report confirms that privatisation has failed to address the needs of the poor worldwide. The report describes the bank’s privatisation policy over the past two decades as “oversimplified, oversold and ultimately disappointing.”

The global water market is characterised by high barriers to entry due to the capital-intensive nature of operations, as well as a geographically dispersed capital structure. Capital structures are high enough to make duplication of infrastructure economically unviable in virtually all circumstances, making the water services a natural monopoly, a concept first introduced by John Stuart Mill as early as 1848. In the case of infrastructure, such as water and sewerage works, it is feasible to construct only one system for one service area. The Nobel laureate Milton Friedman described rather cynically the options for managing natural monopolies as follows: “We can only choose between three evils: private unregulated monopoly, private monopoly regulated by the state, and public monopoly.”

Mainly as a result of these inherent structural features, few significant new companies have entered the global water market in the last decade. The most prominent have been energy companies joining the 1990s’ fashion for multi-utilities, largely by takeover of or joint venture with existing water companies. Therefore, the global water services market is by large dominated by seven “Water Barons,” and the two biggest of these multinational companies have about a 70% share of the current private operations. In some cases, the establishment of joint ventures between multinationals for operational management or concession contracts or setting up consortia with local partners heightens the already high barriers to entry, which are intrinsic to the water market.

Due to the oligopoly characteristics of the market, the competition among the small number of sellers (oligopolists) therefore takes the form of competition for the market (with long-term exclusive contracts or concessions, of the order of 20 to 30 years) rather than competition in the market (i.e. multiple number of sellers competing for the same set of customers).

These unique characteristics of water services are highly relevant when considering whether a particular country’s or city´s services should be privatised. In particular, they should give pause for thought on the issue of competition. Proponents of privatisation argue that the lack of competition in the public sector causes prices to rise to unreasonable levels.

The study by the authors (Hukka and Katko 2003) shows that this is a myth and that privatised water services actually reduce competition. There may be some competition in the bidding for concessions initially, but once the winner is chosen, the private monopoly with shareholders to satisfy needs more revenue than the public one with the consumers’ interests as its primary driving force. In some cases such concessions, like in Barcelona and Venice, have become “eternal”, lasting over a century - without competition. In practice, the situation is much the same in France, where the concessionaires are changed only in some 15% of the cases and operations return to direct municipal management in only one percent.

Furthermore, public undertakings in European Union (EU) member countries must follow the rules and regulations regarding public procurements that open up the market for the private sector in accordance with the principles of the market economy.

Private multinationals do not have to follow the same “rules of the game” as public undertakings, and vertically-integrated multinational water companies have a vested interest in purchasing equipment from and subcontracting services to their own subsidiaries in order to maximise profit from water and wastewater operations to the benefit of their shareholders. Similar practices affect competition in the procurement of external services and goods, undermine the operator’s incentive to achieve efficiencies and may have a significant impact on operating and capital costs. The implications of privileged or exclusive access to subcontracting can be observed in France as well as in transition and developing countries; therefore this “liberalised” situation may be called a monopoly market. In principle, the question also arises, if this could be defined as the abuse of dominant (monopoly) position.

Introducing the principles and practices of the market economy to public services does not necessarily entail giving up ownership of assets or management control. In Finland, and to a large extent in many other developed economies, public-private cooperation in the wider sense, have helped to reduce the expenses of providing water services and improve the performance of the public undertakings that retain overall responsibility for those services.

A very wide range of public/private cooperation options is available to suit local conditions. Outsourcing of non-core operations to private contractors through competitive bidding (Figure 1) is one simple example and is really just an extension of the procurement policy to cover both delivery of services and supply of materials. In such arrangements, the private sector obtains 60% to 80% of the operating expenditure and nearly 100% of the expenditure on capital investment projects. Besides, competition is continuous - not a one-off event occurring once every 12 to 30 years like in management, lease or concession contracts or in “forever” divestiture.

The idea that competition in the water sector could not be introduced enough under public ownership or management is incorrect. It is also misleading to use positive jargons like “opening up the markets” or “liberalising water sector” unless we really mean “opening up the markets for competition for monopolies.”

As for donors, it would be logical that they should first look at their own countries’ development experiences instead of giving privatisation conditionalities for their support and promoting models of which they have hardly any experiences. Thus, the opportunity of developing publicly-owned and -managed water utilities and local private industry should be also given to developing and transition economies.

Public water and wastewater undertakings in North America, Nordic countries, the Netherlands, Germany and Switzerland, are producing highly valued services for the public. Their operations meet the Dublin principle “decision-making at the lowest appropriate level” in addition to the EU principle of subsidiarity and the principles of the market economy ─ simply because the private sector is involved in the operations in a viable way.

Reference:

Hukka J.J. & Katko T.S. 2003.Water privatisation revisited - panacea or pancake? IRC Occasional Paper Series No, 33. Delft, the Netherlands. 159 p. Available: http://www.irc.nl/pdf/publ/op_priv.pdf.

Authors´ Note

The authors, Jarmo J. HukkaandTapio S. Katkoare senior research fellows at Tampere University of Technology, where they head a research team called Capacity Development in Water and Environmental Services (CADWES). Contact: [email protected]; [email protected]