Is Nereda Really a Game Changer?

After 20 years in research and development, the Nereda aerobic granular sludge process is now in operation, with over 10 references globally and 20 facilities planned. What does it mean for traditional wastewater treatment?

By Tom Freyberg

Around the world cities are becoming more populous. Megacities (more than 10 million population) are now common, with Kolkata, Mumbai, Sao Palo, Lagos and Mexico City all joining the line up. And of course overpopulation cannot be talked about without mentioning China.

The country's economic boom recently made the headlines. Mind startling statistics suggest it will soon have the world's first 50 million person city. In less than 10 years, it could home nearly a quarter of the world's 400 largest cities.

At this scale, water provision and disposal will become particularly tough. With urbanisation taking place on such a rapid and unprecedented scale, space will be become a premium. The footprint of proposed water treatment facilities will soon be scrutinised.

Already many cities and industries around the world are facing the challenge to find cost effective, sustainable solutions for sanitation that have a small footprint. This is all while meeting stringent purification requirements.

One Dutch technology claims to hold the answers to these challenges. Called Nereda, it treats wastewater with the "features of aerobic granular biomass: purifying bacteria that create compact granules with superb settling properties".

Invented by the Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands, it has taken 20 years to be developed through a public-private partnership. The private entity in this group is Dutch consultancy Royal HaskoningDHV, with the Dutch Water Boards acting as the public partner.

It's all in the granule

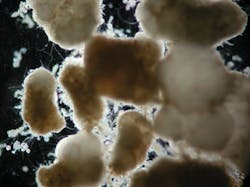

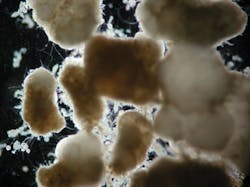

To understand how Nereda works, it's important to first understand the concept of granular sludge. The latter looks like little balls, ranging from a few tenths of a millimetre to several millimetres in size, consisting entirely of bacteria.

Under certain conditions, the bacteria spontaneously clump together to form granules, removing the organic carbon, nitrogen and phosphate from the wastewater. They sink "so rapidly that a sedimentation tank is no longer required", according to the Dutch consultancy.

Anaerobic granules were first identified in the late 1960s by Professor Lettinga, from Wageningen University. Dutch engineering firm Royal HaskoningDHV then became involved with the granular sludge technology in 1999.

For the scientific research, a subsidy was obtained from the STW technology foundation, while financial support for development came from STOWA – the Dutch Foundation for Applied Water Research.

From 2005, the anaerobic granular sludge technology was given the name of Nereda, derived from the name of a water nymph in Greek mythology.

Rene Noppeney, global director for water products at Royal HaskoningDHV, says the secret is in the granule.

"By virtue of the sludge transforming into a granule – two things happen," he says. "One, the granule is heavier – that's Newtonian gravity. That's simple. By virtue of being heavy it settles down quickly. The more quickly it settles down, the less space you need for a settling tank. The second is, within that granule, the bacteria organise themselves very smartly. You have bacteria that use oxygen that sit on the outside. And you have bacteria that don't need oxygen that sit on the inside of the granule.

"In a way, this granule symbolises three conventional steps in a normal activated sludge installation. These three steps that in a normal application take up an enormous amount of space. This now takes place within that very granule. We have learned how to produce such a granule without adding materials or chemicals."

Experience in Epe

When telling the "Nereda story", it's important to go back to May 2012 when the Dutch town of Epe opened the first commercial scale WWTP to use the technology.

The Epe plant consists of the following main processes; inlet works with screens and grit removal, followed by three Nereda Bioreactors and effluent polishing via gravity sand filters. The Nereda Bioreactors has a designed capacity of 59,000 P.E. and treats up to 1,500 m3/h (36,000 m3/day) municipal wastewater with a high contribution of industrial wastewater discharged by surrounding slaughter houses.

Produced effluent quality meets "the highest standards in The Netherlands", according to the consultancy, with total Nitrogen and Phosphorous concentrations lower than 5 and 0.3 mg/l. It's also been observed that even in winter conditions, extensive nitrogen removal could be established at very high biological sludge loads.

Happy marriage or messy divorce?

Following the Epe installation, to date 10 plants are now in operation or under construction in the Netherlands, Portugal and South Africa. In July 2013 Foz, the Brazilian Water Company of Odebrecht Ambiental commissioned Royal HaskoningDHV to help build 10 wastewater treatment plants (WWTP) over the next five years using Nereda technology, at a contract value of 11.5 million Euros.

Three months later and in October 2013 Royal HaskoningDHV signed a cooperation agreement with Imtech Process in the UK with the aim of building between five and eight Nereda wastewater treatment installations.

"Imtech are in dialogue with a number of UK water companies about the Nereda technology and are pleased with the level of interest being shown by the water sector," Bruno Speed – managing director of Imtech, tells WWi magazine.

With Imtech acting as the technology delivery partner, this is a type of relationship the Dutch consultancy is looking for in the other countries.

Noppeney describes the partnership as a marriage: "That model is basically the same in each and every market," he says. "Although you have to recognise that markets do differ from each other. The basics are the same – we're looking for partners to complement what we're doing – a delivery partner for our technology in the local market. Ideally this is like a marriage. We are engaged to be married at this stage. If all goes well in the marriage then you don't need anyone else. That's what we're aiming for."

Industry reaction

Independent wastewater expert Jan Pereboom (formerly Veolia Water Solutions & Technologies) is positive about the granular technology.

Speaking to WWi, he says: "Nereda is a game-changer. SBR technology (Sequencing Batch Reactor) has already been used more and more for sewage treatment over the last decades, manly because the investment cost and space requirements are lower and the technology is more flexible as compared to activate sludge.

"Nereda is also an SBR technology, but has even lower investment and space requirements, while it also has lower operating costs. But most important biological nitrogen and phosphorus removal is more simple and more reliable with Nereda."

While Nereda is now not considered a "new" technology – with the Epe installation now over two years old – the big question is whether utilities will still consider it a risk compared to more traditional techniques.

Pereboom believes even if considered a risk there is a backup plan: "I am afraid that Nereda will only confirm and stress this approach (risk averse) in municipal wastewater treatment. In the orders placed and the plants under construction, there are no additional risks taken by the operators," he says.

"The worse case analysis for these operators is simple; at limited extra investment costs the system can be changed again easily to a conventional SBR plants."

The global push

Noppeney, as you would expect, is confident about the uptake in Nereda technology. He predicts that in five years' time: "I would be disappointed if by then we wouldn't have had 50 installations worldwide".

Alongside Epe in the Netherlands, there are seven other references in the country, including in Rotterdam and Utrecht. In Portugal there is one plant in Frielas and in South Africa there are two references, in Gansbaai and Wemmershoek.

Pereboom emphasises the need for basic infrastructure in developing parts of Asia and Latin America.

"Some 20 clients have ordered this new technology, based on half a dozen plants currently being operated for a very limited amount of years," he says.

"So apparently, these clients are more than convinced that Nereda is indeed cheaper and will perform at least as good. In many regions, for instance Asia and Latin America, sanitation is still under development and numerous sewage treatment plants still have to be constructed."

He finishes by saying that: "the introduction [of Nereda] may be slower in well developed markets" but that "in the Netherlands for instance numerous plants from the 70's and early 80's are considered to be relocated, to free up space for urban development".

The topic of space comes back to the introductory comments about the rise of megacities. While the Netherlands has a lot less space to play with compared to say China, this still shows that even developed countries are looking to shuffle existing infrastructure around in order to house more people. Royal HaskoningDHV claims that using Nereda, a plant footprint can be up to four times smaller with "20-30% significantly lower energy consumption".

With the world's population continuing to grow, it could be the footprint of future water treatment infrastructure that sets it apart in the future.

Tom Freyberg is chief editor of WWI magazine, for more information on this article and Nereda, email: [email protected]