Overcoming water scarcity in Israel

Saul Arlosoroff of Mekorot reports on Israel's comprehensive strategy and policies to enhance its socio-economic growth despite water scarcity challenges. This article follows the author’s overview on water demand management strategy published in the August/September issue of WWI (Vol 21, Issue 4).

Eng. Saul Arlosoroff

The semi-arid country of Israel, populated by 650,000 residents, consumed 300 cubic meters (m3) per person for all uses in 1948. The gross domestic profit (GDP) was then US$ 300 per capita. By 2005 Israel’s population reached seven million, GDP increased to $18,000 per capita, yet water consumption for all sectors remains at approximately 300 m3 of fresh water per capita despite the giant leap in income and population.

Israel experienced economic growth and prosperity despite its limited water supply by implementing water demand management (WDM), a potential and powerful strategy for water-scarce regions. The government launched an intensive national campaign for water conservation and improved water use efficiencies; initiated comprehensive wastewater treatment and reuse, began trading treated effluents with freshwater allocations for farms; and continues to import grains in order to save large quantities of water. Israel balances its agricultural production for consumption goods depending on the development of fresh natural water resources. Government policy favors exports of agricultural products that require less water, and imports of products that require more water. All of these actions comprise the government’s national water resources management and its water demand management strategy.

National Water Resources Management

The Israeli government implemented the National Water Resources Development program and its related Water Demand Management Program (MDMP). Their many instruments and components are explained below.

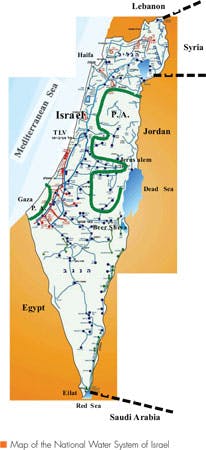

Supply strategy. Nationwide, the government developed surface and ground water resources and constructed regional projects that connect all resources into a network. A national carrier was also constructed to transfer water from the relatively abundant north to the water-scarce center and south. The National Water Carrier (NWC) intersects all regional projects, which completes the National Water System. This investment enables the authorities to maintain a balanced national pumping policy and monitor hydro geological conditions continually throughout the country.

The desalination of brackish and seawater has become the primary way to increase water supply and improve water quality, because natural fresh water supplies and the reuse of wastewater cannot meet all of the growing demands for water.

Demand management strategy

The Israeli government incorporated several instruments into the water demand management strategy in order to achieve its national water demand objectives.

Legal. The National Water Law passed by the Knesset (Parliament) in 1959 declared all water resources to be public domain. It established a water commission to regulate, monitor, and manage the country’s water resources. In 2006 the government passed an amendment to the law forming the Water Authority as the more powerful new regulator on all water and wastewater affairs. A comprehensive water metering law was passed, which led to the completion of a total water metering system. Progressive block rates were set for every farmer, domestic consumer, industry, and commercial consumer. Prices are updated automatically with a cost-of-living formula, incentives for remote consumers are being minimized, and the Knesset approved and implemented water abstraction fees in 2000. Abstraction fees represent the scarcity value of water; it is a unique economic instrument that has hardly ever been used.

The reuse of sewage effluents is an integrated part of the demand management strategy. Regulations are in effect to increase the quality of sewage treatment plants and effluents, in order to maximize its reuse potential, minimize health and environmental risks, and enhance the trading potential for exchanging freshwater allocations, mainly for irrigation purposes. Since the 1990s irrigation allocation policy has concentrated on reducing freshwater use, replacing it with treated wastewater effluents. The city pays total sewerage costs, while the water sector pays for the extra treatment and for the conveyance to irrigation sites.

By 2005 Israel reached a 65 percent reuse level; 50 percent of the total irrigation sector allocation now uses treated sewage effluents.

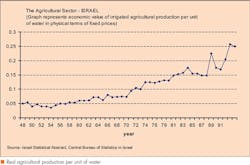

Water conservation/improved efficiency of water use. Continued policies concentrate on mixed tools including: (a) allocations, norms and progressive block rates for each sector; and (b) research, development and implementation of agronomic techniques, including the large scale implementation of drip irrigation techniques, automated irrigation, and changing cropping patterns based on the product value per unit of water and other factors. In addition, the government promotes the development and installation of technically advanced, water-efficient water fittings and systems in the urban, domestic, and industrial sectors.

Water allocation in agriculture and industry. Irrigation water allocations are based on norms developed by the agricultural research institutions together with the farming community. Allocations reflect the potential economic gains by introducing new irrigation technologies, changes in cropping pattern, (e.g. the changes from crops where the product value per unit of water is relatively low, such as grains, for example). Years of research have generated appropriate norms based on modern irrigation technology, including drip irrigation and automation, which are the bases for allocating water to the farming community.

The industrial sector adopted a similar policy that used surveys to determine ways to reduce water usage per unit of product and reduce pollution caused by each industry. Survey results helped to implement policies, set priorities, schedule engineering work, and establish special funding instruments and sanctions. The nationwide program was carried out industry by industry to establish a norm allocation system based on water quantity per unit of production.

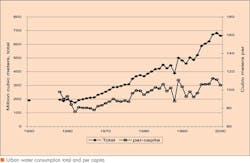

Urban water conservation. Water conservation programs use total water metering and progressive pricing; special funds for replacing older pipes; equipment retrofitting campaigns; and electronic monitoring of the network components regulating flows, pressures, and the identification of major losses. For example, the focus of retrofitting campaigns is on double-volume toilet flushing. Basins were redesigned and manufactured according to enforced legal standards. Flow and pressure regulators for taps and showers were introduced. Parks and gardens began using drip irrigation to conserve water. All of these actions carried out over the past 25 years have decreased water use dramatically. Urban water consumption in Israel has hardly changed on a per capita basis despite an increase of 300 percent in the GDP during the last approximately 40 years. Comprehensive and total retrofitting has yet to be completed.

Virtual water policy. Israeli authorities made the difficult decision in the 1960s to import the majority of its grain products instead of growing it within the country. Officials realized then that the country’s scarce water supplies could not meet this demand. In today’s figures, the volume of imported grain represents the “Virtual Import” of almost three billion cubic meters of water annually -- almost twice the total availability of water resources in Israel.

Water markets (internal and possible external). Government and legislative authorities recently approved a change in the water code that enables holders of water allocations to sell their permanent or temporary allocations. The transaction can be conveyed via the national water carrier, thus opening the sector for market-like operations. The water commissioner office had been trading freshwater with treated sewage effluents for irrigation use for many years. This market approach could promote peaceful exchanges of water between Middle Eastern countries.

Water desalination. Recent dry spells and increasing water demand that cannot be met by natural recharges have led to the government’s decision to initiate and accelerate the construction of reverse osmosis seawater desalination plants. In 2005-2006, the total fresh water available in the country increased by ten percent through desalination projects, increasing water supplies by 100 million cubic meters/year.

Intensive research and development brought about significant cost reductions in RO seawater desalination. In 2001-2001 international tenders submitted to Mekorot, the National Water Corporation of Israel for the Ashkelon desalination project, quoted desalination prices as low as US$ 0.52 per cubic meter, given plant design improvements. Rising energy costs, however, pushed the price up to US$ 0.55 per cubic meter of water since the agreement was signed. In September 2006 a second bid was closed for a desalination plant at Hedera at US$ 0.52 per cubic meter of water.

The new policy calls for nationwide brackish water desalination, and the treatment and reuse of all wastewater in Israel using tertiary and secondary treatment. These new sources will be given to farmers in exchange for their freshwater allocations.

Conclusion

Israel’s National Water Development Program, incorporating the water demand management strategy, will allow the country to continue indefinitely its socio-economic growth despite population growth, improvements in living standards, and limited water supplies. This policy and investments in developing more efficient use of water and wastewater resources will eventually open the door for potential solutions to water conflicts between Israel and its neighbors.

Undoubtedly, the Middle East region will face serious water scarcity crises unless government leaders gather the necessary political courage to adopt and implement comprehensive water demand management strategies.

Author’s Note

Saul Arlosoroff is the director of the board and chairman of the finance committee for Mekorot-- The National Water Corporation of Israel. For more information, contact the author by email: [email protected].