Controlling Urban Runoff with Low Impact Development

By Chris Kloss and Nancy Stoner

Stormwater management in urban areas still bears many of the characteristics of an era when rivers and waterways were viewed as little more than receiving destinations of untreated waste waters. A large portion of the wastewater infrastructure that serves as the foundation of the municipal water management network predates modern water treatment practices. Since the mid-1900s when environmental controls began to be installed to limit the discharge of pollutants, municipalities have struggled to identify the most economically and environmentally effective methods of water treatment. Rehabilitating the nation’s aging and increasingly inadequate wastewater infrastructure system presents an economic challenge that will impact the water quality in urban watersheds and the condition of our built environment.

Stormwater presents both water quality treatment and, in combined sewer systems especially, infrastructure capacity challenges. Effectively managing runoff can be one of the most complex challenges facing urban municipalities. Traditionally, a wastewater approach has been employed to manage stormwater: large, centralized systems are used to collect and convey stormwater away from urban centers. Water quality treatment may be provided for a small portion of runoff (although urban stormwater is largely untreated), but stormwater volume reduction is not. The impervious surfaces and changes in land cover responsible for stormwater runoff go largely unaddressed and municipalities are faced with an increasing amount of stormwater to manage and mitigate.

Green infrastructure and low impact development (LID) practices are now being used in several cities to change how stormwater is managed and complement traditional gray infrastructure. LID techniques use or mimic nature, often capturing and treating rain where it falls, to reduce runoff. By using soil and vegetation as components of the infrastructure system, and allowing rain to infiltrate, evapotranspirate, or be otherwise retained, LID reduces the inflow of stormwater into sewer collection systems. Less water in the sewer system means less pollution discharged from combined sewer overflows (CSOs) or separate stormwater sewers and lower treatment costs at wastewater treatment plants. Cost savings have also been gained from either avoiding the addition of new infrastructure or diminishing the size and scope of capacity improvements.

Portland’s LID program uses a variety of approaches to reduce stormwater inflow into its combined sewer system. The city’s $8 million subsidized downspout disconnection program has saved $250 million in infrastructure improvements by diverting a billion gallons of rain annually from the combined sewer system and allowing the rain to soak into the ground. Innovative streetscape designs have also been used to introduce vegetation into sidewalks, traffic calming devices, and public rights-of-way to manage stormwater at the source. Testing of some of the demonstration projects has shown runoff reductions of more than 80%.

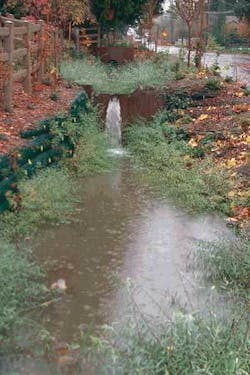

Seattle’s Natural Drainage Systems program has developed alternative vegetated conveyance and control systems to substitute for pipes and culverts. Roadside bioswales and vegetated cascading drainage channels have been installed as pilot projects in a watershed that drains to sensitive receiving waters that are home to salmon. Two of the original pilot projects, the 2nd Avenue SEA Street bioswales and the Viewlands Cascade, have reduced stormwater runoff 99% and 75%, respectively.

LID and green controls also provide other environmental benefits by filtering airborne pollutants, offsetting urban heat island effects, and reducing the heating and cooling demands of buildings. For example, Chicago’s City Hall green roof retains 75% of a one-inch storm event, and temperatures above its surface average 10-15°F lower than those of a nearby black tar roof, with a difference of as much as 50°F in August. The associated energy savings for the building are estimated to be $3,600 annually. The aesthetic benefit of greening urban areas is also a critical factor for thriving and sustainable communities.

Innovative on-the-ground LID applications have often been accompanied by policy and institutional changes that encourage their use. Several jurisdictions have revised their stormwater regulations to place an emphasis on on-site retention and management. For example, in early 2007 the state of Maryland adopted a Stormwater Management Act that stipulates that LID techniques are the preferred treatment method and must be fully utilized before conventional techniques can be considered. Adequate public funding is also crucial for LID adoption. Public financing has been used directly to install pilot projects, subsidize community programs, and provide grant money for private efforts. Chicago’s Department of the Environment announced that it would provide twenty $5,000 grants in 2006 for small-scale commercial and residential green roofs and received 123 applications. Cities have also structured their utility fees to provide a fee discount when green controls are installed.

Finding an effective approach to managing urban stormwater runoff and improving water quality has been elusive. However, with demonstrated successes, several cities are confirming that LID and green controls are an economically and environmentally viable approach for stormwater management and natural resource protection.

About the Authors:

Chris Kloss is a Senior Environmental Scientist at the Low Impact Development Center. Nancy Stoner is a Senior Attorney and Director of the Clean Water Project at the Natural Resources Defense Council.