As water industry experts, part of our job is to read the tea leaves and provide some perspective on what we think will be the most innovative, impactful trends in the year ahead.

Here’s what we see for the water industry in 2020.

Big Tech Disrupts Water Incumbents to Address Key Water Market Challenges

Companies are increasingly turning to digital solutions to help address key water issues dominating the headlines — water quality, affordability, leakage, cybersecurity, and water supply risk to name just a few.

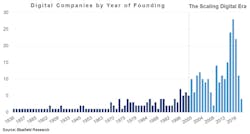

Though the water industry has been flooded with startups — according to Bluefield’s analysis, 61 percent of companies offering digital water solutions have been founded since the year 2000 (see Fig. 1) — sector incumbents have not yet faced significant competition from the Big Tech players shaking up other industry verticals. Software titans like Microsoft, IBM, and Oracle have made only indirect plays in water, by offering cloud services and analytics capabilities to water-focused software firms or selling enterprise solutions built for the electric utility sector opportunistically to large water utilities. As they continue to build out their smart cities capabilities, we expect these companies to expand further into water.

At this time, technology to remove PFAS from drinking water sources, primarily through adsorptive media-like granular activated carbon (GAC) and ion exchange resin, is more mature and established than methods of destroying PFAS, with high-heat incineration the only commercially viable way to break apart the compounds. This suggests that, in the absence of wastewater technologies addressing PFAS, many concentrations will eventually end up in land applications.

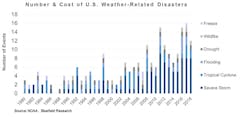

Separately, signals (e.g., temperature, nutrient runoff, larger storm events) indicate Cyanobacterial Harmful Algal Blooms (CyanoHABs) will increase in prevalence and intensity beyond the southern states. Bluefield anticipates that over half of U.S. lakes and reservoirs will be affected by 2022. With over 140 million people served by surface water in the U.S., monitoring for and treating cyanotoxins is an inescapable reality for community water systems. Frustrating as it may be for system operators, it is a considerable opportunity for the water industry because remedial technologies already exist. Technology providers (e.g., activated carbon, polymeric membranes) have readily available treatment solutions and a number of providers are poised to benefit from a US$33 billion monitoring and testing segment.

Back at the Forefront: Lead Pipe Mitigation and How to Pay for It

Five years after Flint, lead is back in the news. Though the U.S. banned the use of lead in new plumbing systems in 1986, lead contamination remains a major challenge for communities across the country. Newark, N.J., is the latest U.S. city thrust into the national spotlight for high levels of lead in its drinking water, inviting comparisons with the Flint, Mich., crisis of 2014.

Lead management remains an intractable problem for U.S. municipalities for several reasons. Homeowners and municipalities share ownership of water service lines, creating uncertainty around who is responsible for paying for the lead remediation. Utilities often have poor data on the locations of lead service lines (LSLs), and compliance with the EPA’s Lead and Copper Rule (LCR) is difficult for municipal utilities to achieve, as it relies primarily on tap samples performed by customers on private property.

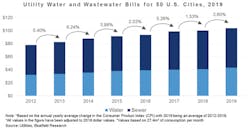

More than 4,600 community water systems — nearly 10 percent of all water systems in the country — have violated the LCR’s monitoring and reporting requirements in the past three years. LSL inventory and replacement programs are extremely costly for cash-strapped municipal agencies. Nationally, the EPA estimates that the cost of replacing all 6.5 to 10 million LSLs in the country could range from US$16 billion to as much as US$80 billion, a figure equivalent to nearly 13 percent of the US$629 billion in total water and wastewater capital expenditures (CAPEX) that Bluefield projects over the next decade.

All Eyes Turn to the Impact of Possible Recession

By September 2019, the U.S. economy had grown for 123 straight months — the longest period on record. Recent indicators, however, signal that a potential shift is underway and beginning to influence strategic planning across the water industry value chain, including hardware and technology vendors, engineering firms, utilities, and investors.

Historically, recessions have had a measurable impact on capital investments in water and wastewater infrastructure with CAPEX growth slowing or falling over the past four recessions. Operating expenditures tell a different story by growing in three of the last four recessions. As forecasted in Bluefield’s recently released CAPEX report, the impact of a possible recession could result in a decline of US$49 billion in investment over the next decade as compared to the status quo scenario (see Fig. 4). The question is when will the water industry know it has arrived at that point?

Big Deals, Big Opportunities Signal Growing Opportunities for Private Players

From established investor-owned utilities to a host of potential outside financial investors refining their strategies to expand or develop their positions in U.S. water utility and asset ownership and operations, private investment interest in water grows. On the heels of the San Jose Water/Connecticut water acquisition, JEA heads to the sales block and Aqua has just acquired DELCORA. At the same time, regional players — Central States Water Group, NW Natural — have added more systems to strengthen growing water portfolios.

Fair Market Value (FMV) legislation is expanding with Texas and Ohio adopting the policy in 2019 (see Fig. 5). Texas is the tenth state to enact an FMV policy, demonstrating a wider acceptance, if not stimulation, of municipal utility consolidation in the water and wastewater sectors. This, and other favorable state policies, continues to drive M&A activity between private buyers and municipalities looking to address aging infrastructure and a lack of funding. WW