Cyanobacteria control in woodland reservoir: Ultrasound and diffused aeration replace copper sulfate

Woodland Reservoir is a 126 million gallon (460,000 m3) man-made reservoir serving as a drinking water supply for the city of Syracuse, located in upstate New York (pop. 148,608 – US Census Bureau 2020). Its water surface area is approximately 14 acres with a maximum depth of 35 feet. The reservoir bottom is lined with concrete and the side walls are faced with rubble masonry laid in cement. Completed in 1894, it is at the receiving end of 19 miles (30 km) of conduits conveying water from Skaneateles Lake (an unfiltered water supply), located in New York’s Finger Lakes Region.

To control algae, the reservoir is manipulated during the summer and early fall, increasing flow to maximize turnover rate, and drawing down the reservoir to expose periphytic growth on the reservoir walls. Adjustments within the water distribution system reduce flow to covered water storage tanks and divert a higher volume of the city’s daily water demand into the reservoir. Maximum daily discharges recorded at the reservoir for July through September typically average 24 to 27 million gallons per day (MGD) allowing for a residence time of approximately five to six days. In comparison, average discharges during the spring and winter range between 13 to 16 MGD.

Algaecide was applied regularly to the reservoir from May through October to suppress algae growth. Treatment began after algae levels cross certain thresholds or water quality in the reservoir was visually deteriorating. As water temperatures increase, cell counts, periphytic growth on reservoir walls, turbidity, water color and clarity were all carefully monitored. The method of application depends on the type of growth; planktonic or periphytic. To treat attached growth on reservoir walls, city employees dragged 50-pound burlap bags of medium crystal copper sulfate around its perimeter or towed the bags along the entire reservoir surface by boat.

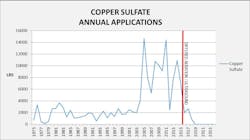

From 1975-2018, at least one copper sulfate treatment was recorded each year for a total of 266 treatments. Over this period, treatments averaged six per year and ranged from 125 pounds (1978) to 14,650 pounds (2005). Figure 1 illustrates cell counts and corresponding annual copper sulfate treatments dating back to 1975. From 2004 to 2015, the reservoir was treated with copper sulfate on 112 occasions, averaging 8,708 pounds per year.

Figure 2 illustrates the dramatic increase in total pounds of copper sulfate applied annually beginning in 2004 because of elevated cell counts of cyanobacteria and their apparent resistance to established treatment amounts. Average annual copper sulfate treatments increased from 1,755 pounds (1975 to 2003) to 8,708 pounds (2004 to 2015). Figure 2 also illustrates the significant decrease in total pounds of copper sulfate applied annually following the initiation of diffused aeration and advanced ultrasonic units.

Treatment effectiveness, which depended on environmental conditions, algae species targeted, cell counts and how uniformly the product was dispersed, varied considerably over this period. Of the 78 treatments recorded from 2007-2018, 22% were still followed by an increase in targeted species cell counts two to four days following pre-treatment counts. Of the 17 targeted treatments for Chroococcus type I (Cyanobacteria, family; Chroococcaceae) during this time, post-treatment cell counts exceeded pre-treatment counts 35% of the time within two to four days of treatment.

Unmanageable algae

In August of 2004 Chroococcus type II cell counts increased from 3,000 cells/mL to more than 28,000 cells/mL within a six-day period despite several copper sulfate treatments. The reservoir was taken off-line, however follow-up treatments of copper sulfate and a liquid, chelated copper formulation did not improve water quality. The reservoir was ultimately drawn down and not put back into service until colder water temperatures resulted in a significantly reduced cell count.

Chroococcus type II cell counts were also very high in 2005 and 2006, accounting for 43% and 26% of the annual cell counts, respectively. Copper sulfate was applied to the reservoir on 15 occasions in 2005, totaling 14,650 pounds — the highest annual amount on record. In early August 2006, 1,500 gallons of an acidified, copper-based algaecide was applied to the reservoir over a two-day period as an alternative to copper sulfate. As Chroococcus type II cell counts increased rapidly in late August, exceeding 3,200 cells/mL, the reservoir was treated with three copper sulfate applications totalling 5,200 pounds within a seven-day period.

Methods

To suppress Chroococcus type II growth, a new strategy using ultrasonic algae control began in 2007. With this approach, soundwaves at the same frequency of algal cell structures reach critical structural resonance (CSR) causing internal wall damage or ruptured gas vesicles depending on the type of algae.

When the inner cell wall (plasmalemma) of algae is torn, internally pumped fluid flow and internal pressure is disturbed, collapsing the inner cell wall and halting nutrient transfer. It also compromises the cell’s defense mechanism, ultimately allowing bacteria to invade and begin digesting the algae. The damaged algal cells begin to float after about three weeks due to collection of digestion gases from internal bacterial attack.

Microcystis aeruginosa, a cyanobacteria, loses buoyancy when the extremely small gas vesicles are internally broken, and the gas they hold slowly diffuses through the unbroken outer cell wall over a period of three to four days.

Gas vacuoles are made up of stacks of cylindrical gas vesicles which are closed by conical ends (Bowen and Jensen, 1965; Walsby, 1994). Lee et al., (2000a) investigated using ultrasonic radiation to damage gas vacuoles of algal cells, causing them to sink within the water column, reducing their access to sunlight. In this case, transmission electron microscopy of the cells showed that the gas vacuoles were intact before sonication and collapsed after sonication. As water depth increases, ultrasonic technology becomes more effective in controlling cyanobacteria.

Full-scale ultrasonic units

Five ultrasonic units of type model SS600 from SonicSolutions LLC were installed around the reservoir perimeter. These devices work by emitting soundwaves from a transducer head positioned just under the water surface, converting electrical energy into sound (mechanical) energy with the sound projected into the water body. Damage results when a target’s natural resonance frequencies match the ultrasonic frequencies emitted by these devices.

The sonic heads each created 18 frequencies with an average difference between frequencies of 1.3% or 580 Hz and a range of about 9.4 kHz, centered on 42.2 kHz.

Although the ultrasonic units initially appeared to be effective in controlling Chroococcus type II cell counts, a new form of cyanobacteria identified as Cyanobium became dominant in the reservoir in the summer and fall of 2007. Unfortunately, the ultrasonic units and copper sulfate treatments were not effective in controlling Cyanobium growth. Monthly cell counts for the summer and fall 2007 season averaged 6,210 cells/mL in July, 6,306 cells/mL in August and 11,997 cells/mL in September.

In 2009, the frequency set was increased to 79 frequencies, the range was about 40 kHz and was centered on 44 kHz with the difference between frequencies at 1.4% or about 525 Hz on average. This was the first attempt at increasing the frequency density to increase the odds of hitting CSR frequencies of more species.

From 2007 through 2015, 77 copper sulfate treatments were applied, totalling 77,850 pounds. Cyanobium was consistently the dominant form throughout this period, ranging from 34.1 to 76.4% of annual cell counts. Elevated cell counts persisted throughout summer and fall, with maximum cell counts for individual months totalling 14,240 cells/mL (July 26, 2008), 17,074 cells/mL (August 11, 2010) and 18,223 cells/mL (September 15, 2014).

Transforming algae control

To address what was becoming an unmanageable situation, it was decided to evaluate the effectiveness of diffused aeration. Diffusers continuously release micro-bubbles typically 2 millimetres in diameter that rise at 1 foot per second through the water column to the surface. As the bubbles rise, they push and drag large volumes of water from the reservoir bottom to the surface allowing for beneficial water movement and mixing. Exchanging gases with the atmosphere induces oxygen-transfer and allows gases such as carbon dioxide to be expelled. Continued mixing of the reservoir allows for uniform chemical and physical properties including temperature and pH.

Since cyanobacteria require extended photoperiods and warmer water, continuously mixing the reservoir disrupts cyanobacteria’s ability to dominate the upper water column. Cyanobacteria cells traveling up and down through the water column encounter a mixture of dark and light environments and cooler water conditions, both of which discourage their ability to dominate in the reservoir.

In 2016 two diffused aeration systems (Robust-Aire Model RA3XL) were installed in the reservoir. The diffusers were positioned in 25 to 35 feet of water, each displacing approximately 16.7 MGD, for a total of approximately 100 MGD. This system pumps compressed air from a shore-mounted compressor through self-weighted tubing to the diffuser stations on the reservoir bottom.

Flow studies, water quality observations and cell counts indicated that stagnant zones form within the reservoir due to the reservoir’s kidney shape and the locations of the inlet and outlet. Since the inlet is located along the south-east perimeter and the outlet is at the north end, influent water can short-circuit along the east side of the reservoir. To enhance mixing, the diffusers were placed along the north-west and south sections of the reservoir as shown in Figure 3.

In July 2017 an ultrasonic algae control unit (Hydro BioScience Quattro-DB) was installed in the reservoir’s north basin. The unit generates more than 1,582 different frequencies in two separate bandwidths. The upper bandwidth targets cyanobacteria like Microcystis using a high number of frequencies (2,024) to ensure the best chance for CSR. A 0.6 second pause is included between each pulse to improve biofilm control in the water treatment facilities. The ultrasonic unit has the same coverage area as four of the diffused aeration units because it emits sound from four emission points; both use 120-volt AC power.

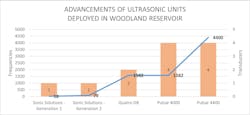

The coverage area for this device includes up to 17 acres for green algae and diatoms (radial range of 150 meters) and up to 120 acres for cyanobacteria (radial range of 400 meters). Additional units installed in 2018 included a larger diffused aeration system (Robust-Aire RA6XL model) in the north basin of the reservoir and a Quattro-DB unit within the south basin. Additional Quattro-DB units were installed in 2019 and 2020. In 2022 a Pulsar 4000 ultrasonic unit manufactured by WaterIQ Technologies was installed in the north basin. A Pulsar 4400 replaced an older generation Quattro-DB unit in 2023. This unit generates 4,400 frequencies and features a consistent and precise microprocessor clock. Figure 4 illustrates frequency and transducer enhancements from the SonicSolutions (Generation 1) device to the Pulsar 4400.

Results

The impact of ultrasonic units and diffused aeration systems has been most pronounced in the reduction of dominant forms of cyanobacteria. Maximum daily cell counts in 2014 and 2015 peaked at 18,223 cells/mL and 15,251 cells/mL respectively, even though the reservoir was treated with copper sulfate on ten occasions in 2014 and eight occasions in 2015. Following installation of the combined technologies, the highest daily cell counts recorded in 2019 to 2024 ranged between 1,710 cells/mL, and 10,907 cells/mL.

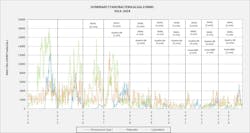

Fig. 5 illustrates the steep decline in cell counts of Chroococcus Type I, Cyanobium and Polycystis, corresponding to additional Robust-Aire diffused aeration systems and Quattro-DB units. Chroococcus Type I, Cyanobium and Polycystis have decreased by 45%, 88%, and 56% respectively from 2014 to 2024.

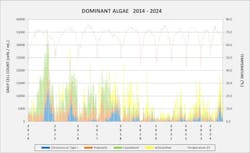

Figure 6 illustrates a significant shift in the dominant species began in 2018. Cyanobacteria accounted for 82% of the annual average cell count from 2007 to 2017, whereas diatoms accounted for just 17%. From 2018 to 2024, annual average cell counts of cyanobacteria remained suppressed, accounting for only 47 percent of cell counts. Diatoms exceeded cyanobacteria as the dominant phylum during this period, accounting for 52% of the annual average cell count.

The steep decline in Cyanobium cell counts from 2014 to 2024 and transition from Cyanobium dominance to Achnanthes dominance in 2018 is apparent in Figure 7. Cyanobium average cell counts declined from 7,175 cells/mL in 2014 to 397 cells/mL in 2020, remaining under 1,000 cells/mL from 2021 to 2024. For the same period, Chroococcus Type I average cell counts declined from 2,440 cells/mL to 136 cells/mL. The average cell count was 171 cells/mL in 2023 and 1,891 cells/mL in 2024. Note the elevated cell counts of Cyanobium and Chroococcus Type I in 2014, despite seven copper sulfate applications totalling 9,650 pounds targeting the two cyanobacteria.

Overall savings

At a contract price of $92.50 per 50-pound bag of medium crystal copper sulfate, the material cost from 2004 to 2015 averaged $16,110 per year, with a total cost of $193,325. Staffing and miscellaneous costs, although difficult to quantify, were a significant seasonal expense, involving a three- to four-person crew to transport, bag and apply the product. Applying copper sulfate in ideal conditions, i.e., full sunlight, and acquiring a dedicated crew available during the peak vacation season posed operational challenges. Continuous monitoring of the reservoir’s water quality through visual observations, cell counts, and physical parameters (temperature and turbidity) added up to many hours, especially in the late summer and fall months.

To reach the goal of eliminating copper sulfate treatments in the reservoir, the city invested a total of $26,056 in diffused aeration units and advanced ultrasound algae control devices from 2016 to 2019. The average annual algal control material cost throughout the four-year transition phase was $9,081 (diffused aeration and ultrasound units: $6,514; copper sulfate: $2,567). Employing additional and improved units and devices within the reservoir produced consistently exceptional water quality and suppressed daily cyanobacteria cell counts with consecutive years (2019 to 2024) of no copper sulfate applications following 44 years of treatment. As a result of lower cell counts and improved water quality, algal monitoring and cell counting activities have been gradually reduced from a total of 67 days in 2014 to 29 days in 2023 and 37 days in 2024.

Seasonal operation and maintenance of the ultrasonic algae control units involves approximately a half-day of installation in the spring, monitoring, and removal of biofilm / mineral deposits on the transducers in the summer/fall, then another half-day removing and cleaning the units in the fall. Basic maintenance of the diffused aeration systems consists of cleaning or replacing air filters and cleaning the compressor cabinets. Following two to three seasons of operation, or if reduced air flow or preferential air flow is observed between diffusers, the compressor piston cups must be replaced. Compressor rebuild kits supplied by the manufacturer are serviced in the field; the kits include cups, cylinder, gaskets/ O-rings, and valves.

Acknowledgment: The author would like to thank Kaylyn Dion, Environmental Engineering, Syracuse University 2020 for her valuable contributions to this article. Special thanks to technical contributors/reviewers; George Hutchinson and Kenneth Rust and technical reviewers, Dan Robbino and Mike Cole.

References

Centre for Aquatic Plant Management (CAPM)

2003 Annual Report

Sonning-on-Thames

Berkshire, England

Lee, T.J., Nakano, K., Matsumara, M., 2000a. Ultrasonic irradiation

for blue-green algae bloom control. Environmental

Technology 22, 383e390

Bowen, C.C., Jensen, T.E., 1965. Blue green algae: fine structure of

gas vacuoles. Science 147, 1460e1462

About the Author

Rich Abbott

Rich Abbott is a public health sanitarian with the Syracuse Water Department. Abbott oversees the city's ultrasonic anti-algae deployment.