The fundamental purpose of a wastewater collection and treatment system is to protect public health. To do this, it’s critically important to keep wastewater in the wastewater collection system. Toward this goal, it’s also critical to keep extraneous groundwater and surface water out of the wastewater system. Sanitary Sewer Overflows (SSOs) are generally attributed to infiltration and inflow (I&I) overloading sewer systems to the point where wastewater exits the collection system at utility maintenance holes and/or basements.

Infiltration describes groundwater that infiltrates a sewer system through defective pipes, pipe joints, connections, or utility maintenance holes. Inflow is any water other than sanitary flow that enters a sewer system, from sources like drains from wet areas and surface runoff. Both can wreak havoc on a sewer system, but there are wastewater collection options available that can help reduce or eliminate I&I, including a liquid-only sewer system.

A typical liquid-only sewer system generally consists of onsite processor units and small-diameter, pressurized collection mains. While concrete interceptor tanks are still used in some applications, emerging tank materials like dicyclopentadiene (DCPD) are becoming more widely used. The processor unit located at each property provides primary wastewater treatment, allowing the system to only pump effluent, which drastically reduces the size and magnitude of the wastewater collection mains. Most importantly, a high-quality liquid-only sewer system is designed to be watertight.

The city of Yelm, Wash., located at the south end of Puget Sound, receives 48 inches of rain and 6 inches of snow annually, with precipitation falling 167 days per year. According to U.S. Census data, there are 3.19 people per household in Yelm, with a total population of 9,570.

The city’s 27-year-old wastewater collection system consists of 40 miles of liquid-only sewer mains and more than 3,000 active wastewater connections. The system uses concrete interceptor tanks that can develop leaks with age.

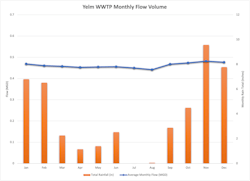

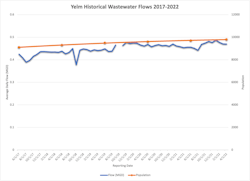

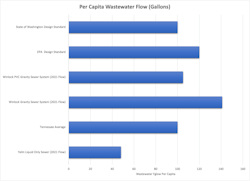

These flow rates equate to approximately 46 gallons per capita per day (gpcd) at the lowest, 48 gpcd on average, and 50 gallons gpcd during peak flow. If we assume that the lowest monthly flow volume is the dry-flow rate, which is reasonable since there was little to no rain during this period, I&I is in the range of 4.1 percent of the total flow volume. The minimal amount of I&I in Yelm is likely attributed to joints in a concrete tank, pipe inlets or outlets, or possibly the riser-to-tank connection. DCPD tanks would be expected to mitigate these possible I&I points.

By contrast, a four-year study in Tennessee estimated that 45.38 percent of the flow to the state’s 227 municipal wastewater treatment plants was attributed to I&I. Furthermore, two-thirds of the wastewater plants in Tennessee have wastewater flows that include more than 50 percent I&I. The lowest I&I, as a percentage of total wastewater flow, was greater than 15 percent. The state of Tennessee receives 51.6 inches of annual rainfall and 4.1 inches of snow on average, correlating very closely with precipitation averages for Yelm.

In another comparison, the cities of Winlock and Vader, both in Washington State, completed a joint I&I study of their gravity sewer system in 2013. In the study, the City of Winlock had slightly more than 10 miles of gravity sewer pipe; 69.8 percent of the system was PVC pipe with the remainder asbestos concrete, ductile iron, and clay, with 59.5 percent of the laterals being PVC. There were 476 homes connected to the Winlock system with approximately 2.6 people per household. According to the 2021 State I&I Report, wastewater flow averaged 174,000 gallons per day (gpd) or 366 gpd/equivalent dwelling unit (EDU). I&I averaged 102,000 gpd or 82 gpcd, if we assume that the lowest monthly flow represents the dry flow. The 2013 study stated that the Winlock base flow is 80 gpcd.

While it would not be appropriate to compare I&I from non-PVC systems to Yelm, Basin F from the Winlock/Vader study was 100 percent PVC. Basin F had 12,938 lineal feet of gravity main and 41 PVC laterals. This basin accounted for 5 percent of the I&I found in the 2013 study, which would conservatively translate to roughly 5,100 gpd I&I or 25 gpcd of I&I, on average. Peak I&I in Basin F has been more than 50,000 gpd or approximately 6 times base flow. When evaluating wastewater collection options, it’s common practice to assume that PVC gravity systems don’t leak. However, the data from Winlock shows that I&I in PVC gravity sewer systems does occur.

The most commonly referenced document defining the derivation of wastewater flow rates is the Federal Register (1989), which states “The Agency (EPA) has determined that the correction of excessive infiltration is likely to be unsuccessful for sewer systems with a dry weather base flow of up to 120 gallons per capita per day (gpcd). This figure is based on the following typical values: 70 gpcd domestic wastewater flow, 10 gpcd commercial and industrial wastewater flow, and 40 gpcd nonexcessive infiltration flow.” The City of Yelm is much lower than the EPA baseline domestic wastewater flow.

Generally, most states use design guidelines that define wastewater flow per EDU (Equivalent Dwelling Unit). This design flow rate is typically anywhere between 200 gpd and 350 gpd per EDU. This value is inclusive of appropriate I&I reserve, both immediate and long term. The State of Washington uses 100 gpcd, which for Yelm would translate to 319 gallons per EDU daily.

I&I entering a wastewater collection system will necessitate additional treatment capacity, additional conveyance capacity, and additional costs for pumping and treatment.

Additionally, treating I&I can lead to inefficient treatment and illicit discharges. The City of Yelm has a connection fee of $6,394 for each EDU of wastewater capacity. Due to very low I&I, this saved capacity has a value of almost $20 million to the city if future connections are all liquid-only sewer. If we conservatively assume that treatment costs are in the range of $2-$5 per 1000 gallons treated, Yelm is avoiding approximately $350,000 to $875,000 in additional treatment costs each year.

Finally, the cost to remove I&I from collection systems is very expensive. AT Hampton Roads Sanitary District (HRSD) in Virginia, I&I removal costs worked out to $7.91/gallon of I&I removed in the public right-of-way and $3.59/gallon of I&I removed in private service laterals. HRSD noted that completing repair and replacement (R&R) work on 90 percent of the systems only removed 63 percent of the I&I. If Yelm were a similar gravity sewer system, this would translate to approximately 300,000 gpd of I&I that could be removed at a capital cost of $2 million.

The value of a watertight wastewater collection system is not often calculated and understood. However, the benefits are quantifiable and significant. In the case of Yelm, the city is receiving measurable cost savings from having a liquid-only sewer system with very little I&I. As designers and engineers strive to create more resilient infrastructure, considering I&I and designing ways to eliminate it can benefit communities — and their bottom lines — for decades to come. WW

Published in WaterWorld magazine, September 2022.