Ozone-biologically activated carbon has been in use at drinking water treatment plants for years. However, the benefits of such technologies are now being acknowledged at wastewater treatment plants for water reuse applications.

By Vijay Sundaram, Lucinda Jooste, Melanie Holmer and Allegra da Silva

Pressures on traditional water resources have pushed communities around the world to evaluate various options for expanding resources, including potable water reuse. By 2050, scientists predict that population and economic growth will result in an additional 1.8 billion people globally (representing a 53 percent increase) living in regions with high water stress, largely in emerging markets.

After the “low-hanging fruit” of water use efficiency and consumption reductions are maximised, alternative water sources are an appealing option, as interbasin transfers and overdrawing conventional supplies can have major social, environmental, and political ramifications.

Historically alternative water sources have only been sought by communities faced with severe water scarcity. However, a relatively new driver is the fact that tightening requirements for wastewater discharges (including low nitrogen and phosphorus limits, as well as limits on trace chemical constituents such as pharmaceuticals and endocrine disrupting compounds) may mean that, in some locations, highly treated wastewater effluent may be of higher water quality or more reliable treatability than conventional drinking water supplies. The feasibility of potable reuse depends largely on the local regulatory context, costs and social acceptability. In addition to the increasing interest in reuse from communities, industrial water reuse is seeing its own coming of age story with electric power, oil refineries, upstream oil & gas, and data centers all emerging as key users of reclaimed wastewater - each with its own unique treatment requirements.

Water reuse is outpacing desalination and has seen tremendous growth over the past decade with significant investments planned or executed in US, China, Saudi Arabia, Australia, Spain, Mexico, UAE, Oman, India, Algeria, and South Africa.

Focus on potable reuse

We now have the technology to treat wastewater to any desired quality – to potable quality or beyond (for example, for microchip manufacturing). Cities throughout the world have been able to extend water supplies further by capturing wastewater, treating it to very high standards, and using it for landscape irrigation, food crop irrigation, toilet flushing, industrial, and other non-potable uses. Designer waters are being implemented in a variety of regions and industries to provide tailored reused water to efficiently use this precious resource.

Expanding agricultural use of recycled water is particularly attractive, since agriculture uses around 70 percent of the world’s freshwater supply on a global scale. However, with the exception of pockets of truly urban agriculture, often sources of recycled water are not located close to major agricultural centers. The next major user of freshwater is urban use – municipal (drinking) and industrial. If we are to move the needle on alternative water supplies, both potable and industrial reuse will have to play a major role in cities throughout the world.

Industry buzz

While historically membrane treatment, such as reverse osmosis (RO) has been the backbone of multi-stage treatment approaches for potable reuse, ozone biological filtration (BAF) has the reuse industry buzzing with real promise to transform water supplies for global communities.

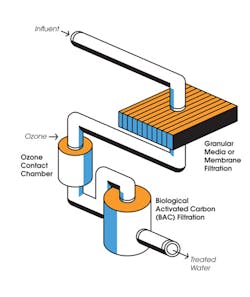

By incorporating ozone-BAF technology, reuse/drinking water augmentation projects can address trace chemical constituents, including contaminants of emerging concern (CECs) and pathogens. Ozone-BAF technology consists of ozonation and biological activated filtration treatment processes. Very often the filtration technology is activated carbon, and the process is termed ozone-biologically activated carbon (ozone-BAC). The purposes of this technology in reuse applications are to remove CECs, refractory organics and pathogens.

When using ozone-BAC an upstream filtration step is typically included to reduce suspended solids and turbidity. Ozone-BAC has been in use at drinking water treatment plants for years. However, the benefits of ozone-BAC at wastewater treatment plants for water reuse applications are being widely reported and acknowledged within the past decade.

One of the earliest wastewater ozone-BAC field performance evaluations was performed by consultancy Stantec and the City of Reno from 2008 to 2010 at the Reno-Stead Wastewater Reclamation Facility. CEC removal in ozone-BAC was achieved mainly via three treatment mechanisms: 1) oxidation, 2) biodegradation, and 3) adsorption. Since then, several full-scale ozone-BAC projects have now been implemented in New Mexico and Texas.

Case study: South Africa

The City of Cape Town, South Africa has been facing severe drought since 2011, finally resorting to level five water restrictions in May 2017, which has helped the city extend supplies. Current supplies in the city’s dams are projected to run out in March 2018, prompting dramatic conservation efforts, network improvements to reduce inefficiencies, improved metering to reduce demand, emergency groundwater extraction, rainwater capture and storage, and major investments in desalination and water reuse, including direct potable reuse.

On a national basis, the country is facing a 7-22 percent deficit by 2030, depending on development of new supply systems. The projected markets for industrial and municipal potable water reuse in the Western Cape are R600 million (US$44 million) and R4.5 billion (US$300 million), respectively. While reverse osmosis has been implemented in South Africa (e.g. in Beaufort West) and will continue to play a large role in the growing DPR market because of the country’s coastal location, ozone-BAF is being trialed for DPR in Darvill (Kwazulu natal), as well as for crop irrigation in DE Doorns.

Public support

The last decade has marked a dramatic shift in public perception and acceptance for water reuse. Two decades ago, negative public perception effectively relegated water reuse as a non-starter in many communities, including San Diego. Fast forward to 2017 – the Pure Water San Diego Program has initiated final design for a 114,000 m3/day purified water facility to deliver water to the Miramar Reservoir for ultimate treatment at Miramar Water Treatment Plant. Once unthinkable in San Diego, several multi-year droughts in combination with an extensive public outreach and education campaign have allowed for an atmosphere where the majority of residents support potable reuse and recognise its pivotal role in water reliability.

Integration of potable reuse into mainstream culture is slowly gaining momentum in a unique and surprising way – using purified water for beer brewing competitions (including home brewers and microbreweries) organised by water reuse associations and communities. These and similar events provide experiences that, while valuable in education, can help shift the way the public thinks about purified water in a fun and engaging manner.

Seeking a higher purpose

As communities and industry move toward applications and technologies associated with fit-for-purpose water, the debate will inevitably shift to reusing water for its highest purpose. For example, does it make sense to provide advanced treatment only to pump that highly treated water into the ground? Is landscaping irrigation the best and highest use for this alternative water supply, or does potable reuse serve a higher purpose? Communities juggle limited resources and must make decisions based on reliability, resiliency and sustainability.

Water is a limited resource, and conservation is an important tool in a community’s toolbox for water sustainability. However, as population grows and with more frequent and longer-lasting droughts, water reuse – in particular, potable reuse – is an option that can serve to bolster water security and stability for many communities.

Vijay Sundaram is a regional practice leader in wastewater, Melanie Holmer is the California region practice lead for water and Allegra da Silva is the Rocky Mountain Region practice lead for water reuse at Stantec. Lucinda Jooste is from Xylem.

More Water & WasteWater International Archives Issue Articles